Rabbis Today and Yesterday

Who is a rabbi?

Jewish children with their teacher in Samarkand. Photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky. 1911 / Wikimedia / US Library of Congress Collection

A rabbi (from the Hebrew Rav, “teacher,” “mentor”) is a person who heads a Jewish religious community of a synagogue, of a neighbourhood, or an entire city.

The institution of rabbis emerged in the Middle Ages. Initially, the heads of the Babylonian diaspora appointed counsellors and judges to the local communities. Around the 10th century, as the Babylonian centre declined, the communities began to seek and elect their spiritual leaders.

Initially, a rabbi received no financial remuneration in exchange for his work since it was believed that the Torah should not be taught for money. Consequently, the rabbi would earn his living through some trade or craft. Gradually, being a rabbi became a separate profession: Asher ben Jehiel (13th century), appointed rabbi of Toledo, was paid a salary by the congregation; this was probably not an isolated case.

Over time, being a rabbi became a common Jewish profession, a fact quite tellingly attested by the prevalence of last names such as Rabinovich, Rabin, Hacham (the title of rabbi among Oriental Jews), etc.

Below we will discuss a rabbi's role in the past and how it has evolved presently.

Is rabbi a Jewish priest?

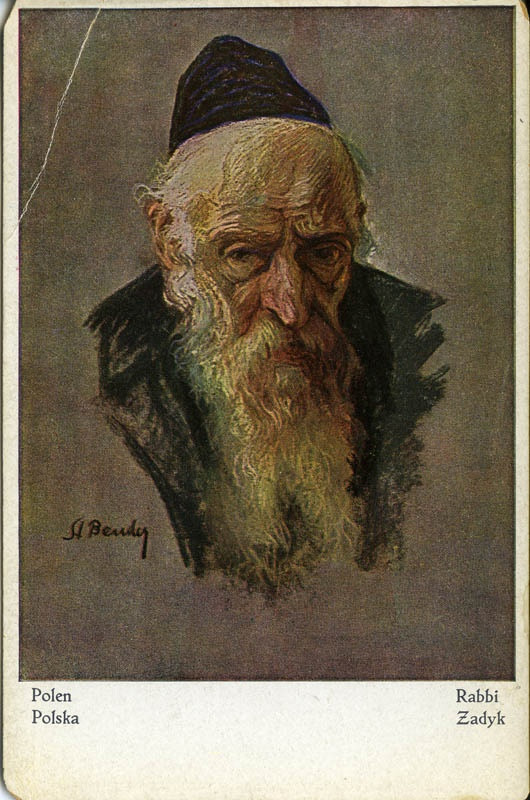

Rabbi. Author: St. Bender. Munich, Germany. The first half of the 20th century / Yeshiva University Museum

No. Moreover, there is hardly a more inadequate definition! The institution of priesthood does exist in Judaism: the Jewish priests (kohanim) are the descendants of Aaron, Moshe's brother, who were given the exclusive right to offer sacrifices. As long as the Temple existed, the priests were naturally in charge of the religious and at times, also of the political life of the Jewish people. Today, however, their unique role is limited to a few ceremonies, and they have no direct bearing on spiritual leadership; they are ordinary “lay” Jews.

Unlike the Christian priest, who holds an exclusive right to perform certain ritual acts (“sacraments”), a rabbi is an ordinary Jew with a profound knowledge of Jewish law.

Sometimes synagogues and even entire communities can do without a rabbi at all. And, accordingly, any Jew who has demonstrated his knowledge and abilities can become a rabbi.

How does one become a rabbi?

It is very simple: one must study Jewish religious law (the halacha) exhaustively and demonstrate knowledge to a renowned Torah scholar. Today, future rabbis usually study in special religious institutions: yeshivas or seminaries (in the case of the non-Orthodox). But theoretically, one can also prepare externally by studying Torah with private teachers.

From the fifteenth century on, candidates for rabbinical ordination are required to present a smicha, a letter of recommendation from a renowned Torah scholar, confirming their level of learnedness. At first, this custom was somewhat contested since some zealous defendants of faith saw in it an emulation of non-Jewish customs. Over time, however, this practice became universal.

Although rabbis are commonly portrayed as grey-bearded older men, in the past, rabbis would often obtain their rabbinical credentials at a very young age. For instance, future Israeli Minister of Education Ben-Zion Dinur (Dinaburg, 1884-1973) became a rabbi in 1902 at 18. Rabbi Yehiel Yaacov Weinberg (1884-1966), who later became one of the leading religious authorities in Western Europe, received his smichah at 19; the future Soviet Commissar Semyon Dimanstein at the age of 17, etc.

What does a rabbi do upon receiving his credentials?

“Portrait of a Rabbi with a Prayer Scroll.” Isidore Kaufmann. / Wikimedia

Looks for a place. In the old days, one would likely become a rabbi in a small shtetl. Presently, most rabbis work in synagogue congregations.

The election of a rabbi could be carried out in several ways. Sometimes several candidates would be “courted”. If the previous rabbi had a worthy son, he would inherit the position (Der Nister, “The Family Mashber”):

In the same month of Nisan, during Passover, Rabbi Reb Dudi, famous in the city, passed away...Before the grave was filled up, they shouted, looking inside it: “And your son Leyser will take your place... And the city commits itself to respect him since he is worthy of it.”

In some cases, rabbi's seats could simply be bought. For example, in 1750, the wealthy Yehuda Safra paid 37,000 zlotys to have his son-in-law become rabbi of Vilna, the most prominent Jewish community in Poland then.

Presently, a rabbi is usually hired by the congregation's leadership or the synagogue, either by recommendation or interviews. A rabbi may be sent to it if the congregation isn’t particularly robust. Sometimes such envoys build communities from scratch.

What was the rabbi's job?

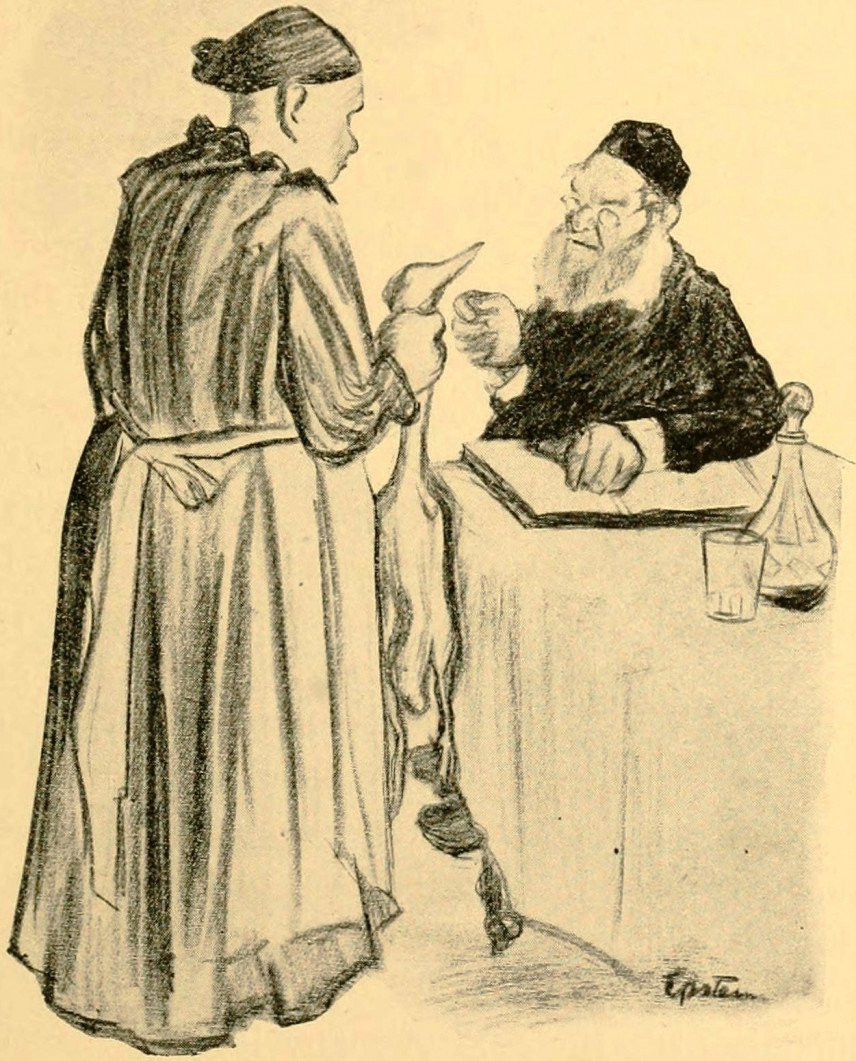

“A rabbi can tell if it's kosher.” Illustration by Jacob Epstein. 1902 /U.S. Congress Library Collection / Wikimedia

As we have said previously, a rabbi is an expert in Jewish law. Therefore, in the past, rabbis mainly answered countless questions from their congregation members concerning kashrut, Shabbat, and family relations...

This is how the writer Mendele Mocher Sforim describes it in “The Little Man”:

“Ah, Benya!” says the rabbi.

“What can I say? I'm taking a nap and hear peek, peek, peek. The rooster and the hens are eating a piece of bread. I take a spoon and go to the chickens. I hear something boiling over in the hearth, so I put the meat spoon not into the hens—but into the milk pot...

“How big is the pot?”

“It's bigger than my head.”

“Kosher!” the rabbi decides.

The server's wife entered. She had a sheet under her arm. “I want to bother you with a “woman’s” matter…”

Moreover, rabbis oversaw animal slaughter and often sat as judges.

In today's world, a rabbi's duties are far more varied, especially in small communities. The rabbi is sometimes a jack-of-all-trades: performing the prayers, reading the Torah, blowing the shofar, preaching, running a Jewish school, etc.

Was the rabbi supposed to teach Torah?

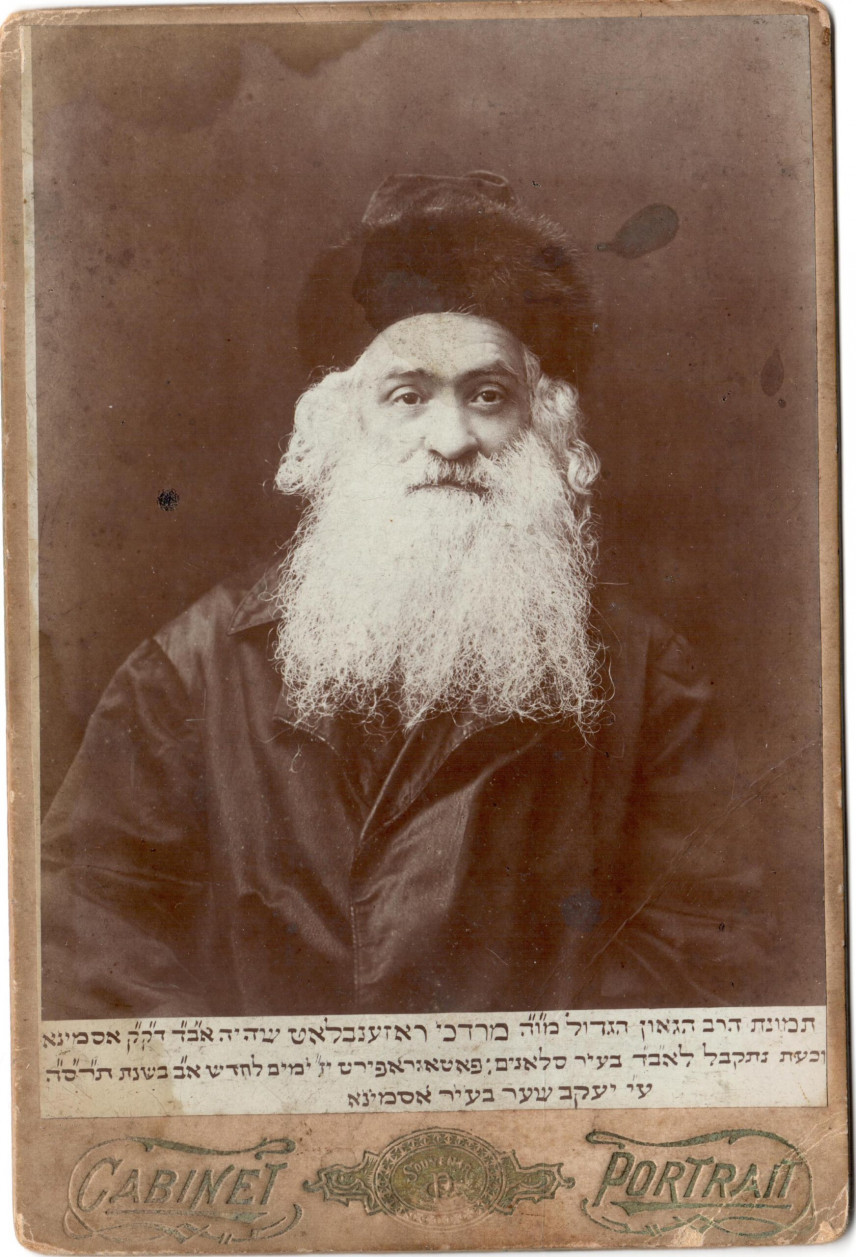

Mordechai Rosenblat, Rabbi of Slonim. Slonim. 1905 / CAHJP, RU-1225/1

In the past, it depended on the terms of the contract. For instance, the contract signed by one Shaul-Zelig with the Pruzhany kahal had the following clause:

We undertake to follow his instructions. He will receive a wage of 5 rubles... He is to teach in the synagogue until noon.

Besides, many rabbis would conduct Talmud classes without any contract, usually for the most capable and advanced students. Sometimes a yeshiva would be formed around a rabbi, attracting local youth and outsiders. For example, Rabbi Yaakov-David Wilovsky, having become rabbi of Slutsk, established a yeshiva there in 1900.

This is how it is described in the “Memorial Book of Slutsk”:

The “voice of the Torah” was heard from every synagogue; in every prayer house, young men were studying the holy books on their own. Boys of eleven years and older enrolled in yeshivas. Most came from small towns around Slutsk, but some came from Bobruisk, Mozyr, etc.

Presently, teaching Torah—lecturing, giving lessons, etc.—is one of the rabbi’s primary duties.

Did the rabbi have responsibilities in the synagogue?

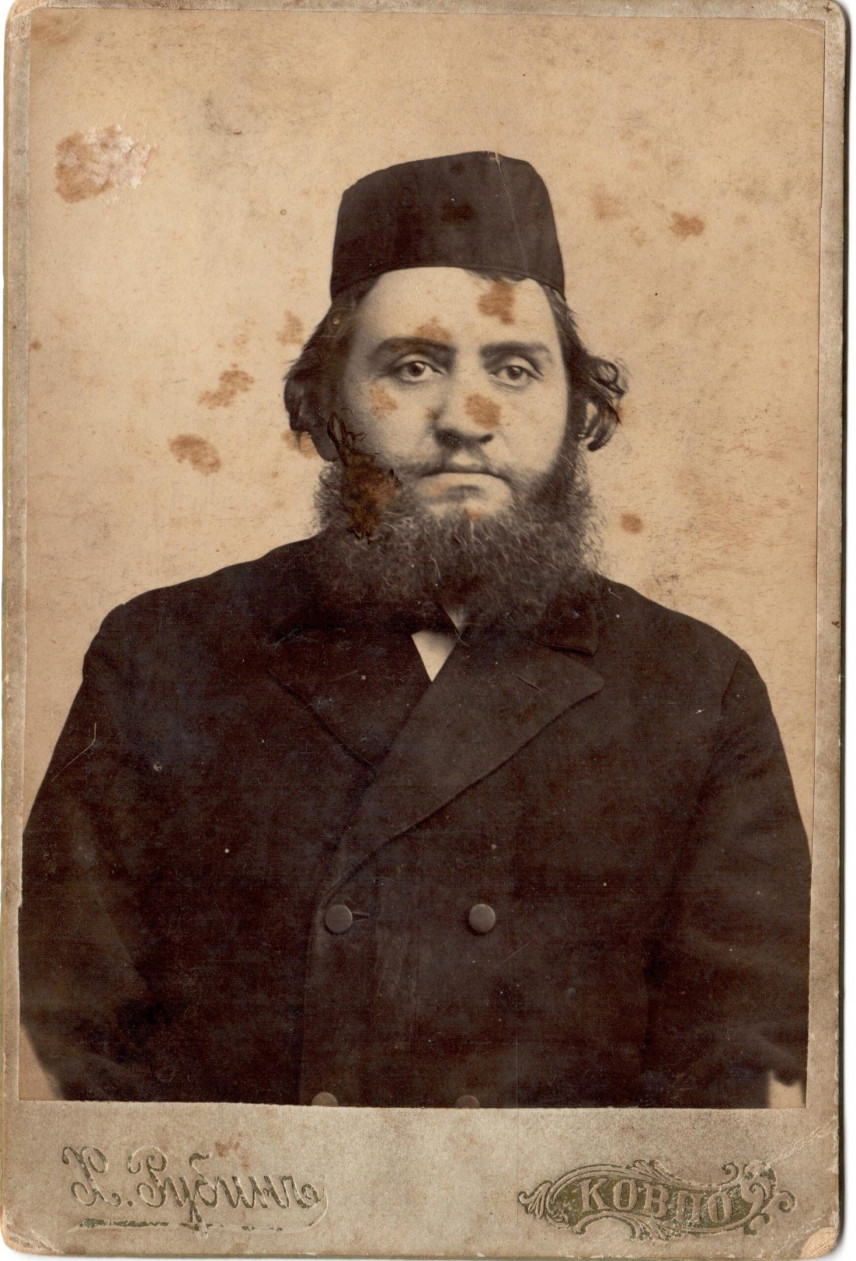

Yudel Berstein, the last rabbi of Gorky. 1904 / CAHJP, RU-1225/2

In the past, only very few. They usually consisted of two sermons per year: one on the Sabbath before Passover (Shabbat ha-Gadol) and the other on the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement (Shabbat Shuvah). In the former, he would remind the Jews of the Holiday's laws; in the latter, he called for repentance.

Others performed all other duties. The synagogue headman (gabai) supervised the services, the cantor (hazan) led prayers, and the preacher (magid) preached sermons.

In the nineteenth century, under the influence of Christians, the situation began to change: first among the Reformed and then among the Orthodox as well, rabbis began preaching sermons regularly. This usually happens on the Sabbath (during the evening and/or morning services) or Jewish holidays. The starting point for such a sermon is most often the weekly chapter. Here is a description from Harry Kemelman's book, “Saturday the Rabbi Went Hungry”:

The sermon discussed this portion of the service. Comparing this with Abraham's attempted sacrifice of Isaac—a reference to the New Year reading on Rosh Hashanah, the beginning of ten Days of Awe.

How did the relationship between the rabbi and the congregation develop?

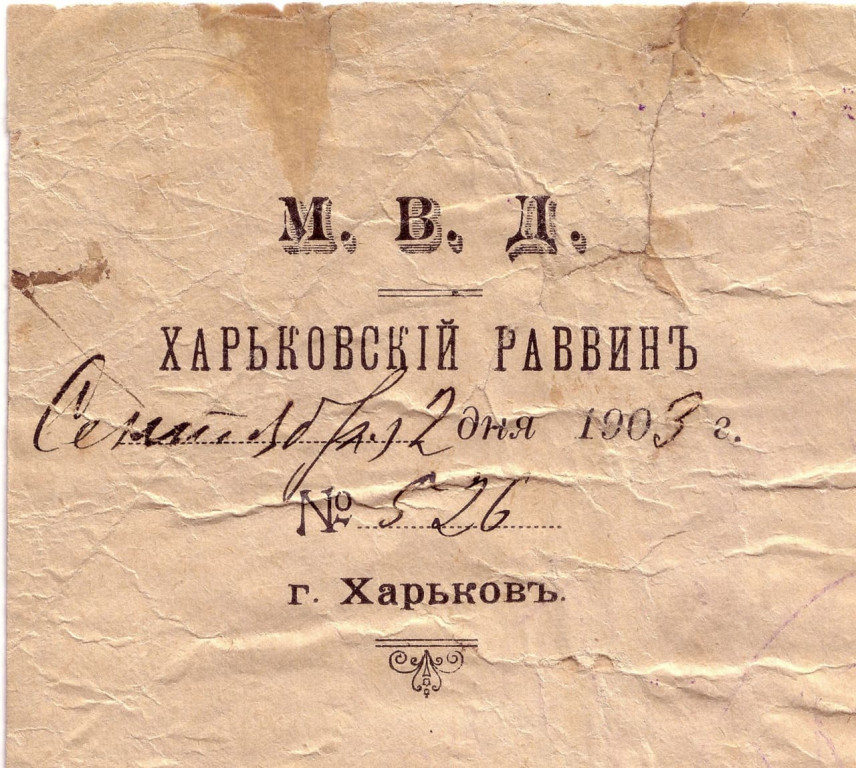

The seal of the rabbi of the city of Kharkiv. 1903 / Wikimedia

It depends. On the one hand, the rabbi was a “hired employee” of the kahal and relied heavily on its leadership. In Jewish literature, there are many rabbinic complaints about the despotism of wealthy merchants, tax collectors, and other Kahal chiefs.

On the other hand, the rabbi had many means of enforcing his decisions: fines, cherem (exclusion from the community), and sometimes even corporal punishment and imprisonment. For example, the rabbi of the town of Zaludno, upon learning of a young maiden’s frivolities, ordered her to pay a fine, after which she would be paraded through the streets of the town to the beat of the drums. On another occasion, when a local butcher was found in the wrong, the rabbi revoked his right to slaughter animals. The butcher offered to pay a fine of 50 rubles, but the rabbi declined. Then the butcher complained to the town’s landlord and got the following response: “Your rabbi is an honest man; you won't find another like him“. Generally, everything depended on how well-respected the rabbi was in his community. In this sense, nothing has changed since then.

What makes up a Rabbi’s livelihood?

The American researcher Isaac Levitatz cites a typical early nineteenth-century contract signed by Rabbi Shlomo ben Chaim with the Bialystok kahal. The rabbi was entitled to small weekly wages, as well as a free apartment and payment for “special services”: “For each sermon one gold chervonets; for each wedding ceremony a due percentage”. Other sources of income included divorce proceedings, litigation, sale of contracts, etrogues, and more.

Smaller communities, naturally, offered poorer conditions: in some places, the rabbis were not paid at all, granted in return an exclusive right to sell some common commodity, such as kerosene. The poorest would pay their rabbi in kind. Yechezkel Kotik (1847-1921), who grew up in the town of Kamenetz, recalls the town rabbi:

He received three rubles a week in wages and sat day and night with the Torah. The rabbanit tried to persuade her husband to ask for at least another ruble a week, but he would not ask for anything.

The modern rabbi receives a salary and fees for “occasional services”. Many have part-time teaching positions.

Can only men be Rabbis?

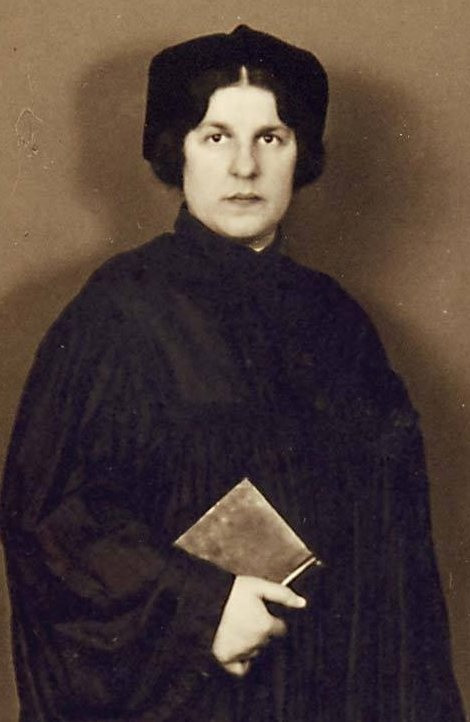

Regina Jonas, the first woman rabbi. 1939 / Wikimedia

Historically, rabbis were exclusively men. This is still the case for the vast majority of modern orthodox congregations.

Non-Orthodox movements, first the Reform and then the Conservative, accepted women rabbis in the twentieth century. The first was a German Jewish woman named Regina Jonas, who received ordination in 1935. In November 1942, she was arrested and deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp, where she gave lectures and talks on religious matters for two years and provided spiritual support to fellow prisoners. On October 12, 1944, Jonas was sent to Auschwitz along with most of the Theresienstadt inmates.

The first woman to receive rabbinical ordination and lead a congregation was the American Sally Prisand in 1972. For all the liberalism and progressivism of the American Reform movement, back in the day, it took her almost ten years to secure a Rabbi’s position.

Today, non-Orthodox women rabbis no longer surprise anyone. A few years ago, Alina Traiger, a native of Ukraine, joined their ranks.