Course

Where in the world did Rabinovich come from? All about Jewish surnames

What do surnames Schwartz, Marshak and Rosenberg say?

What did Katz, Kogan and Schulman do?

What do Chaimovich, Raikin and Viktorov have in common?

Who were the neighbours of Shapiro, Teplitsky and Sverdlov?

This material is a brief history and overview of Jewish surnames. If your family name is something like "Rachlin", then you are likely to be interested in "Honour thy father and thy mother ..." section, and if it's something like "Steinberg" - check out the "Situation in Germany and Austria" section. As a rule, one can find surnames of different origin and meaning in a history of a Jewish family and by looking at them we shall learn where our ancestors came from or where they wandered and what their occupations were. Such knowledge helps us better understand our people' history.

A long way to surnames

Odessa Jews. XIX century drawing. Illustration from book: "Essays on the history

and culture of Jews in Ukraine" (Ukr.). Kyiv, 2005. p. 71

"Regulation on Settlement of Jews" issued in Russia under Alexander I in 1804 contained the order to all Jewish subjects of the Empire to assume family names. This was part of the extensive reforms conceived by the authorities regarding the Jews. The family names being inherited did not immediately take root though, it took quite a few years.

So what was the case with surnames among the Jews prior to this? As historians rightly point out, there were no surnames in the modern sense of the word. Historically, the Jews were accustomed to refer to a person by their name and their father's name when addressing or mentioning them. Therefore, heroes of Jewish history, even when referring to outstanding individuals, are simply called "Moshe ben Amram" or "David ben Ishai" in Haggadic stories and Midrash. And everyone has a clear idea of who is being referred to. Alternatively, there can be a different approach, that of including a reference to a person's role or merit in his or her name: "Moshe rabeinu" or "David a-melech". As a matter of fact, this rule has persisted in the Jewish tradition to this day, which is why many characters in Modern Jewish history are known as "Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo-Zalman'' (the Vilna Gaon) or "Rabbi Yisrael ben Eliezer'' (the founder of Hasidism Baal Shem-Tov, or Besht). As for the latter example, it reveals another anthroponymic principle: a name (later established in a surname) can be taken from a nickname emphasising a distinctive feature or characteristic, or from an abbreviation of a famous ancestor's name. Thus, long before the surname campaign, there appeared in Jewish practice Maaral ("Moreinu ha-rabi Leo") or Maharshak ("Moreinu ha-rabbi Shlomo Kluger"). These appellations might not necessarily be passed on to descendants, but they were certainly retained forever for the famous individual, helping to preserve his memory and ensure infallible identification.

Situation in Germany and Austria

Polish Jews. 19th century drawing. Illustration

from History of the Jewish People in Russia.

Vol.1. Moscow-Jerusalem, 2010. p. 272

In the 18th century, European nations engulfed by the Enlightenment saw the onset of changes that would also affect Jewish communities. In some German principalities and kingdoms, particularly in the multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire, a movement seeking Jewish empowerment and exposure to European culture was gaining momentum. One of the tangible results of the Enlightenment, or Haskalah as it is commonly referred to in Jewish historiography, was the adoption of the European name-giving tradition. This was visible among the Jews of Germany and Austria by the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Among the notable figures of that time were Joseph Süßkind Oppenheimer, the "Court Jew'' of Württemberg who lived a bit earlier (commonly known as "Jew Süss," although it's worth noting that he was also known by his traditional name Joseph ben Issachar), the Haskalah ideologue Moses Mendelssohn, and Heinrich Marx, a lawyer from Trier and the father of the author of Capital, who converted to Lutheranism for career reasons (a characteristic case: born with the name Herschel Levy Mordecai, he was the son of Rabbi Marx Levi Mordecai)."Levi" presumably indicates the priestly origins of the family, its descent from the Levites. Acculturating into Prussian government officialdom, the lawyer adopted the name "Heinrich", taking his father's first name as a surname, which, in turn, is a germanised rendering of Mordechai). Then one can mention the writer and translator Ernst Dom, who before his baptism bore the name Elias Levi, or the family of the industrialist Rudolf Pringsheim, which produced a number of prominent scientists (the mathematician Alfred Pringsheim and his son Peter). These facts demonstrate that the Jews of German lands adopted German surnames, or at least German-sounding ones, whilst embracing the local language and culture. In doing so, many of them, while embracing the dominant culture, remained Jewish by faith.

In the Austrian Empire, the most notable contribution to streamlining the Jewish surnames was made by the enlightened monarch Joseph II.

It was under his reign that there began a rapid transition by the Jewish population over to the daily lifestyle of those around them, and it is primarily in Austria that the large group of surnames now widespread among Jews originated. Above all, these were surnames arbitrarily coined by civil servants, the most popular being Gross, Klein, Weiss and Schwarz (each having merely the meaning of the corresponding German word), or the grand-sounding, but equally meaningless Rosenberg, Steinberg, Apfelbaum or Horfunkel. Such officials, greedy for bribes, could bestow a fancy surname on a person in exchange for a bribe. Likewise, they often ended up giving unpleasant surnames to the emperor's subjects, such as Drachtenblut (dragon's blood) or Ochsenschwanz (bull's tail), if they were denied a reward or were otherwise upset.

Russian empire, following tradition

Synagogue sexton. Illustration from Essays on the History

and Culture of the Jews in Ukraine (Ukr.). Kyiv, 2005. p. 259

Thirty years before the Regulation on Settlement of Jews the Russian Empire took in new subjects following the partitions of , and at first did not know what to do with them. The Russian authorities had little interaction with Jews until then, and the few who appeared in historical records typically had traditional names, often consisting more of patronymics. For instance, there was Borokh Leybov, a figure in the so-called "Voznitsyn Affair," which involved a Russian officer converting to Judaism.

The situation started to change in the early nineteenth century, and the range of Jewish surnames started gaining in diversity such as we know it today. It was certainly based on pre-existing principles: abbreviated names of Talmudic authorities (Marshak, Roshal, Barash) or special religious terms (Katz, Shatz, Shub, etc.), denoting the descent from the Kohen and Levites (Kagan, Kaganovich, Kagan; Kaplan; Levin, Levite, Levitan, and many other variations). That said, some other principles emerged too, resulting in dozens and hundreds of new surnames.

Melamed in cheder. Illustration from Essays on the History

and Culture of Jews in Ukraine (Ukr.). Kyiv, 2005. p. 296

The range of occupational surnames: professions and community functions

A carpenter. Illustration from Essays on the History

and Culture of the Jews in Ukraine (Ukr.). Kyiv, 2005. p. 98.

Primarily, these are surnames derived from the names of occupations. Among these were Jewish community functions (rabbi – Rabin, Rabinovich, rabbi's assistant – Podrabinek, synagogue sexton – Shulman or Shkolnik, cantor – Cantor, Hazan (Hazanov), Spivak, community attorney – Neeman (Neiman) or Vernik (Vernikov), cattle slaughterer – Reznik (Reznikov), Shoykhet; Melamed – Melamed (Melamid, Malamud), teacher – Uchitel; teacher's assistant – Belfer or Belferman; menaker (one who checks the removal of the carcass vein and belly fat) – Menaker; and such rare "professions" as "Messiah's watchman", in Polish Dozorets, hence the surname Dozorets) are also included in that group. By way of example in this group we see that the surnames were derived from corresponding Russian or Hebrew words, occasionally words from Polish, Ukrainian or German. All the other groups too retain such linguistic diversity. A further observation is that parts of words from different languages can occur together when forming a surname, for instance, when a Russian suffix was added to a Hebrew root, as in the surnames Kaganov, Khazanov or Levitov. Another conclusion can be drawn that the German suffix -man (also found in Yiddish) comes into active use in the formation of surnames. In fact, it is the word-forming equivalent of the Slavic suffixes -ov and -ovich and conveys the meaning of "person", "son of so-and-so".

Stonemason. Illustration from Essays on the History

and Culture of the Jews of Ukraine. Kyiv, 2005. p. 98

In the crafts circle

Merchant. Illustration from Essays on the History

and Culture of Jews in Ukraine (in Ukr.). Kyiv, 2005. p. 106

The vast majority of occupations of Jews in Russia were related to crafts and trade, and this fact is reflected in the surnames that were adopted.

The most common among the Jews were probably the trades of dressmaking and shoemaking, giving rise to a set of surnames like Hayat, Shneider (Shneiderov, Shneiderman), Portnoy (Portnov), Kravets; Sandler, Schuster (Schumacher), Sapozhnikov and some others. Another observation is pertinent at this point. Obviously, not all tailors or shoemakers were Jews, which is why there are so many Kravtsov, Kravchenko, Shvetsov, and Shevchenko among Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians. Kravets and Sapozhnikov are not necessarily Jewish either. A general approach to formation of surnames is at issue here, and the surname history of each individual family can be quite diverse. The historical context and the specifics of Jewish life in Russia must be taken into account when examining another set of surnames – those denoting an affiliation to the winemaking trade. Now this profession was predominantly Jewish, so the surnames Vinokur, Schenker (and its heavily altered version "Vanshenkin"), Pivovar, Vinokurov are usually Jewish (or belong to descendants of Jews), which, of course, does not prevent exceptions to the general rule.

The great variety of trades within the Pale of Settlement, and towns outside it, where the in-demand craftsmen and their families could settle, gave rise to the surnames of coppersmiths (Kuperschmid, Kiperwasser), dyers (Farber, Farberov, Krasilshchikov), casters (Gisser), smelters (Gamarnik), glassmakers (Shklar, Shklyarov, Glaeser, Glaeserson, Lusternik), tinsmiths (Blecher, Blecherov), masons (Broek, Bruckmann), goldsmiths (Gold, Goldschmidt, Silberschmidt), bondmakers (Bondar, Bondarchik, Bednarchuk), printers (Drucker) and water truckers (Wasserman). Immersing ourselves into the economic (and by extension cultural) history of the Jews of Russia, we are confronted with an almost inexhaustible plethora of occupations, each of which may have given its practitioner and his progeny a surname.

"Commercial" surnames also have their own set – Koifman (Kaufman), Kramer (Kramarov), Factor (Faktorovich), Korchmar.

Honour thy father and thy mother…

A Jewish woman dressed for a Sabbath. XIX century drawing. Illustration from

The History of the Jewish People in Russia". Vol. 1. Moscow-Jerusalem, 2010. p. 278

Parents, probably like in many other nations, play a very important role in the Jewish tradition. That is why so many surnames (although other reasons may also apply) are derived from the names of either the father or the mother. One can see, that if in respect to surnames derived from the father's name Jews do not really differ from other peoples, what does in fact set them apart is the abundance of surnames derived from the mother's name, which reflects the very special position of women, or mothers, in the family and in the cycle of Jewish life in general.

In this way, surnames are formed both with the help of the suffix -ov (Aronov, Leiserov, as well as the widespread among Mountain and Bukharian Jews varieties like Pinkhasov, Isakov, Avshalumov, Ilizarov, Ifraimov), and suffixes -evich, -ovic (Haimovich, Berkovich, Gershkovich). A whole number of such surnames can be identified as exclusively Jewish by the characteristic diminutive suffix -chik (Rubinchik - from the name Reuven, Vigdorchik - from the name Avigdor). However, a number of surnames formed from the Jewish male names by means of the suffix -ov are not Jewish (Abramov, Moiseev, Samoilov, Yakovlev): such names were given to orthodox children according to the christian church calendar. Naturally, this does not mean (as in the case with occupational surnames) that Jews never used them – here we are dealing with an area where different traditions overlap.

In some rare cases, the initial origin of the surname is obfuscated, and only a linguistic study can reveal its history. For instance, the Russian surname "Viktorov" goes back to the Jewish "Avigdorov", having undergone a number of transformations.

There are many more derivative models based on feminine names. Here we encounter surnames with the suffix -in (Leikin, Raikin, Mirkin, Elkin, Esterkin, Chernin), with some names producing multiple variants (Raikin – Raitsis, Beilin – Beilis), while others are homonymic to Russian noble surnames (such as Bunin, derived from "Bunya", the surname owned not only by the great writer, but also by the nobleman Afanasii Bunin, father to the poet Zhukovsky). One can also come across surnames with the suffix -man (Gitelman), -enko (Rachlenko), -ind (Rivkind. Etkind).

Perpetual wanderers

Jewish communities in Germany (from Martin Gilbert's Atlas

on the History of the Jewish People)

A large group of Jewish surnames are derived from the names of towns and settlements (toponymic surnames). This approach to anthroponymy goes back to the Middle Ages. As early as then, hereditary nicknames of Minz (from the town of Mainz) or Averbach (or Auerbach, the respective town) are recorded among Ashkenazi Jews. Some of these surnames have come a long way, so that the original name of the town is not always easily recognisable. Such are the surnames Shapiro (from the German town of Speyer), Lifshitz (from Czech Libshice, via German transmission), Gordon (from Belarusian-Polish Grodno). Jews, whether individual merchants and craftsmen or entire communities, frequently resettled; some would spend years travelling. Having arrived in a new place, a person would acquire a nickname indicating the place of his birth or his former dwelling, and would be referred to by that. Associated with this is a peculiarity of toponymic surnames: the name of the settlement they retain refers not to the current, but to the former place of residence, so that, say, "Brodsky" is not a resident of the town of Brody, but a newcomer from Brody. Another way in which such surnames proliferated was through rabbinic responsa – halakhic elucidations sent out on behalf of authoritative scholars and copied by communities. When a rabbi was mentioned, it was customary to state where he lived, thus the name of the town came to be gradually assigned to his descendants.

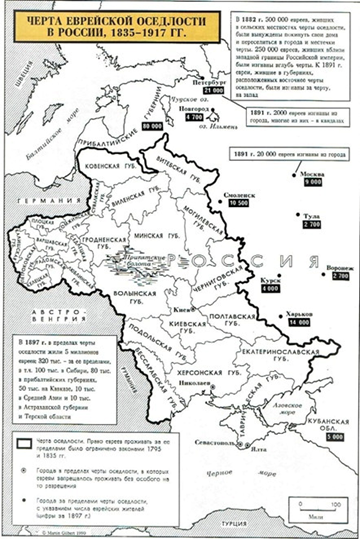

Geography of the Pale of Settlement in the Russian

Empire (from Martin Gilbert's Atlas of Jewish History)

On the map of Russian Empire

A Jew on the street of a settlement. Galicia, early 20th century.

Illustration from Essays on history and culture

of Jews in Ukraine (Ukr.). Kyiv, 2005. p. 268

Toponymic surnames of the Pale of Settlement demonstrate vast variety of stems and suffixes. Any town or settlement of Poland, the Baltic, Belarus or Ukraine (its Galician and Austrian territories as well as those within the borders of the Russian Empire) could in general give rise to a surname. Even today, two hundred years later, the geographical areas of settlement of the Eastern European Jews remain deeply embedded in many surnames of their descendants, scattered across the globe. There is also another observation regarding geographical surnames: when there is no direct trace of a name or occupation that the surname could have originated from, and there is no indication of its origin at first glance, one should have a closer look and try to identify a settlement with a similar name. Given the poor education of registrars and errors in documents, surnames were at times bizarrely distorted. Most surnames derived from settlements of the Russian Empire had the suffix -sky, and in this they are very similar to Polish and Ukrainian surnames (one must consider a surname to be Jewish when it refers to a town or settlement with a predominantly Jewish population, such as Berdichev, Teplik, Uman or Shklov – therefore Berdichevsky, Teplitsky, Umansky and Shklovsky are Jewish surnames, and hardly ever occur among Ukrainians or Belarusians). Another derivational model follows the German pattern – with the suffix -er (Berliner, Warshaver, Kovner, Willner). Rarer are the surnames with the suffix -ov/-ev (Lioznov, Nevelev, Sarnov, Sverdlov) or -in (Blinkin, Briskin). There are also variants of the same surname (Warshaver-Varshavsky, Sverdlov-Sverdlin, Wilner-Vilensky, Lemberg-Lemberger-Lembersky (from the German 'Lemberg' - Lviv)). In the latter case, there is also a parallel Lviv-Lvovsky.

One should not forget the fact that in the days of conscription under Nikolai I, when Jewish children were conscripted as cantonists, many of them lost touch with their families, and even in case they did not convert to Christianity (and many were prompted to do so), their surnames would change. Some were given the surnames of their Russian officer commanders. In such cases, it was as if the family history was starting over, the descendants of the canton officers being largely unaware of their ancestors' origins.

Conclusion

This coherent and multi-faceted system underwent certain changes in the 20th century: the Soviet Union conducted a campaign to Russify first and last names and many Jews adopted aliases. During the years of "the war on cosmopolitanism", some zealous activists were persistent in exposing these aliases, but on the whole to no significant avail. Many prominent individuals – writers, actors – have made history under aliases. Conversely, in the early decades of the State of Israel, there came to be a practice of changing surnames into Hebrew ones, with its founding fathers leading the way: Green became Ben-Gurion, Meerson became Meir, Chertok became Sharet.

But then this process came to a halt, and now there are a plethora of surnames in Israel, in keeping with the local population's diversity.

Studying Jewish surnames is an essential and fascinating part of the history of the Jewish people. And even when we think we know pretty much everything, there is always a surname whose origins are difficult to account for. After all, Chekhov was not so wrong when he once wrote in his notebook: "There is no one thing that would not make a good Jewish surname".

Other courses

Jews in the Weimar Republic Cinema