A Jewish Narcom (People’s Comissar)

There were quite many Jews in Russian early twentieth century revolutionary movement

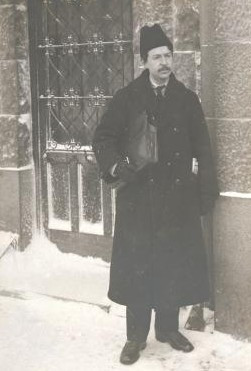

People's Commissar of Justice of the RSFSR Isaac Steinberg, January 1, 1918 / Wikimedia

This is unsurprising: the Russian Empire's laws were outright discriminatory regarding national minorities (and Jews in particular). That said, most of the Jewish revolutionaries renounced Jewish traditions for obvious reasons: the revolutionary movement was, for the most part, progressivist, atheist, and internationalist.

And yet, some adherents of traditional values remained even in the revolutionary milieu

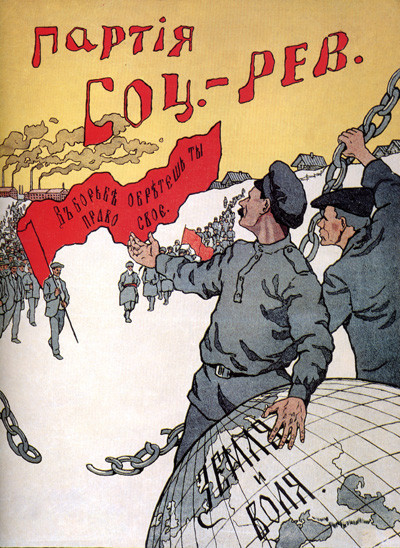

Election poster of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. 1917 / Wikimedia

Future People's Commissar of Justice Isaac Zakharovitch Steinberg was one of such adherents. Steinberg's biography as a revolutionary was quite typical: he first studied in a cheder, then in a gymnasium, then at the university, where he joined the SR, and he was exiled to Tobolsk province... In short, nothing extraordinary except for one thing: Isaac Steinberg remained an observing orthodox Jew. As his brother Aaron Steinberg recalled, because of this, Isaac even had to spend an extra three days in prison:

"The warrant for his release arrived in Moscow on the first day of Shavuot, when one cannot write, and he refused to fill out the form. Our parents travelled on foot from Lefortovo to see three halakhic experts (B. Vishnyak, I. Gavronsky, and R. Gots) so that they make a ruling allowing their son to write; they agreed to consider such a ruling as pikuach nefesh, saving of a life, and then our parents made a second journey on foot, from Moscow city centre to Lefortovo to deliver this ruling to their son. Only then did he fill out the form and leave the prison, having spent extra three days there.”

Steinberg's religious views persisted even after the victory of the revolutionary movement

After the February Revolution in 1917, he was elected a delegate of the Ufa City Duma. Since sessions were also held on Saturdays and there was no eruv in the city, Ufa residents would often see Steinberg hurrying to the Duma accompanied by a “shabesgoi,” carrying his briefcase for him.

Steinberg was repeatedly asked how he managed to combine Judaism and socialism. He would answer that he was a member of the Socialist Socialist Party, which opposed private land ownership, and that it agreed with the Torah, as it says: “The land must not be sold permanently, because the land is mine” (Leviticus 25:23).

Left SR Steinberg entered the Soviet government

Session of the Council of People's Commissars. January 1918 / Russian State Archive of Social and Political History

After the October Revolution of 1917, the Left Socialist Revolutionaries formed a coalition with the Bolsheviks.

Steinberg (who was elected on the party list to the Constituent Assembly) was appointed Commissar of Justice by the Soviet government. He is remembered primarily as a consistent opponent of arbitrary revolutionary violence, terror and repression. Thus, as early as December 1st, 1917, he condemned the anti-Kadet decree, declaring once and again that such unjustified repressive measures as proclaiming the Kadet Party illegal and arresting its members were unacceptable methods for waging class warfare.

In doing so, Steinberg was probably guided by general considerations of humaneness and justice. The commissar might, however, also bear in mind that one of the titles Jews refer to God in their prayers is “Liberator of prisoners”.

Steinberg had other motives besides religion

Inevitably, the Commissar's activities had a somewhat commercial aspect – the government assigned a “ransom” for each liberated individual, as Dr Ivan Manukhin, an activist of the Political Red Cross, wrote:

“The then Commissar of Justice was a left S.R, I. Z. Steinberg. A gentle, compassionate man, as a member of the new government, he was bound by a decree of the Bolshevik majority and, following this decree, demanded that each prisoner pay a certain sum for his release on bail. The size of the fee varied depending on the Commissar's evaluation of how much of a ‘bourgeois’ the person in question was. One had to bargain.”

Steinberg passed to be an enemy of the Bolsheviks

Smolny Institute, Seat of the Soviet government until March 1918, early 20th-century postcard / Wikimedia

The coalition between the Bolsheviks and the Left Socialist Revolutionaries was short-lived and fell apart as early as 1918. After leaving the post of People's Commissar, Steinberg continued his public and political activities (for instance, he spoke on behalf of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries at Kropotkin's funeral) and was arrested several times. However, unlike many of his fellow party members, Steinberg managed to emigrate safely from Soviet Russia. He settled in Berlin, one of the then capitals of Russian (as well as Jewish) emigration.

In 1933, the Nazis came to power in Germany, but Steinberg got lucky again. In the same year, he left the country and lived in England, Australia, Canada and the United States until he died in 1957, taking an active part in Jewish life. This time, however, it was an ordinary career in Jewish affairs, with nothing particularly Russian o revolutionary about it.