The Road Goes into the Distance: A Real Commentary

Vilna—a provincial and European town

by the article's author.

Aleksandra Iakovlevna Brushtein's trilogy The Road Goes to the Distance, written during the "," became to many readers a major source of information about the life of Jewish (and not only) intelligentsia at the turn of the 19-20th centuries. What can we learn by carefully reading the trilogy and its commentaries?

The city where the trilogy by Brushtein is set is not referred to but is perfectly recognizable. In pre-revolutionary Russia, it was called Vilna; in interwar Poland, it was called Vilno; today, it is Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. In her preface to the Lithuanian edition of The Road... Aleksandra Brushtein writes:

I have always remembered that the first sky and the first sun over my head were the skies and the sun of Lithuania. The first beauty I saw with my eyes - those of a child still - was the marvelous architecture of my hometown, where every gray-rock remnant of the stunningly beautiful old architecture is memorable to me. And then there was the beauty of the charming, mild Lithuanian nature - Antokol, Vilija, and Vileika, the gently undulating skyline of the Castle Mountain with the other Vilnius mountains crowding around it, like sisters.

In the trilogy, all these toponyms are more than just mentioned—they are the coordinates of the world in which Sasha Yanovskaya and her friends are growing up. Little Sashenka travels with Yakov Efimovich along Vilenskaya Street past the Governor's Palace, St. Catherine's Church, and the drugstore "Under the Swan" on Ostrabramskaya, and on the way back, they “carouse" in the Theatre Square. The mother of a sick Polish girl, Julka, is ready to crawl on her hands and knees "all the way to the Calvary Church" and pray all day long at the chapel of the miracle-working Catholic icon of Our Lady of Ostrabrama. On Castle Hill, a cannon is fired every day at noon (cannon shots were discontinued in 1909, the trilogy spanning the period from 1892 to 1902). Yulka's mother and her husband, Stepan Antonovich, wait in a restaurant at the Botanical Garden; from there, Sasha and Yulka watch the two flights by hot-air balloonist Drevnitsky.

On the one hand, at that time, Vilna was a deep province of the Russian Empire. As Tomas Venclova puts it, "After Muravyov, from a city of palaces and churches, Vilna turned into a city of prisons and ." The city still lacked a sewer system (instead, there were the "rinnstocks"—sewage ditches running along the pavements), and its provinciality was apparent even to a child's mind. After the 1863 Polish uprising was suppressed, the Polish theater and university, one of the oldest in Europe, were closed in Vilna. As early as first grade, Sasha is confronted with the fact that Polish girls are not allowed to speak their mother tongue but are well aware that "it used to be Poland and not Russia" here. At the turn of the century, Vilna was a multilingual city of ethnic minorities. This is also naively reflected upon by the ice cream man Andrej:

According to the national census of 1897, there were a total of 154,532 people living in Vilna. Of them, 28 638 were Orthodox, 1 318 were Old Believers, 56 688 Catholics, 2 235 Lutherans, 63 986 Jews, and 842 . Meanwhile, at the turn of the century, new centers of culture emerged here: Vasily Kachalov and Vera Komissarzhevskaya made their Russian theatrical debuts here. The Jewish youths eager to receive education rushed to this city, too (remember the story of one of the episodic characters - the boy Pinya). It was precisely then that Vilna took on the 'Jewish Jerusalem' role. In Brushtein's trilogy, many aspects of Jewish culture and everyday life are Russified to one extent or another, and yet it is clear that in her family, her grandparents speak Yiddish (“Vilna Yiddish” became the linguistic norm); Manya Feigel's father works in a “Jewish two-class elementary school,” and Sasha's mother is doing Jewish charity work among the Jews.

Family—the said and the unsaid

Alexandra Brushtein / Photo provided

by the author of the article

Aleksandra Brushtein's real last name was Vygodskaya. The Vilna census of 1876 listed her paternal grandparents: Johel Vegodski, son of Mendel, head of the family, 49 years, a merchant of the second guild, and his six sons ( other sources indicate seven) and his wife - Fonia (Ronja) Vegodski, daughter of Gabriel. The seven sons' names were Yakov, Noy (Nikolai), Meir (Miron), Gabriel, Lazar, Shloim, and Abram, and the only daughter, who had died at the age of two, was Gitel. In his memoirs "Yunge yorn" ("Young Years"), Yakov Efimovich Vygodsky wrote:

Yakov Vygodsky graduated from the Military Medical Academy in 1882, interned in Vienna, and, in 1884, started his medical practice in Vilna. During World War I, he was sent to a camp by the Germans for advocating the non-payment of contributions that they had imposed; in 1918-1919, he served as Minister of Jewish Affairs in the Lithuanian government, and in 1922 and 1928, was elected to the Polish to represent the ethnic minorities block. In 1940, a very old man, he was in charge of aiding German refugees fleeing German-occupied Poland; on August 24, 1941, he was arrested and died in Lukiškės Prison at the end of the year.

The oral testimony of her relatives suggests that Alexandra Brushtein had long believed that her parents, like most Vilna Jews, had been killed in Ponary. She received the news of her parents' death while still in evacuation, probably from composer Maximilian Steinberg. She learned the horrible particulars of the Vilna ghetto from Avrom Sutzkever's book ( surviving in the writer's archive with extensive notes) and from her meeting with Shoshana . Elena Semyonovna Vygodskaya perished after her husband, but the exact place and time of her passing are unknown.

Sasha's mother's maiden name was Iadlovkina. Her father was Semen Mikhailovich (Shimon Mikhelevich) . Like J.E. Vygodsky, he was a graduate of the Medical-Surgical Academy, from which he graduated in . He served as a physician in Kamenetz-Podolsk male grammar school; in 1878, he fought in the Russian-Turkish war. In the "Russian Medical List," published annually and listing every doctor in the empire, S.M.Yadlovkin was last mentioned in 1888. His first wife's name was Shosha (Alexandra) Bloch; they were married in December 1859. They had a son, Michel (Michail), in November 1860 and a daughter, Gena (Elena), in October 1862.

- Do you know who this is? - Mother asks.

- Of course I do! This is my late grandfather...

Yes. And my father..." Mother cleans the frame and the glass affectionately.

Education

by the author of the article

Like all children in those days, Sasha Yanovskaya was homeschooled at first: first, she was given a German bonne, Fräulein Tsetsilhen, who was not exceptionally bright but taught Sasha to "tattle in German" (with the next German tutor, they went on to read Schiller's ballads), next came a French woman, Pauline Picard, the remarkable "Paule," who became not merely a tutor but also a dear friend to the girl. Before entering a gymnasium or an institute, Sasha studied under Pavel Grigorievich Rozanov; his prototype, as Brushtein herself admits, was Pinhas Isaakovich Rosenthal - a prominent member of the Bund, a revolutionary and the inventor of the secret code. Like Ya.E. Yanovsky, he was educated in a cheder till the age of nine, then in the gymnasium, and upon graduating from it, he was accepted to the Medical Faculty of Kharkiv University. In the trilogy, Pavel Grigorievich's exile to Siberia preceded his arrival in Vilna, whereas, in reality, it was the other way round: he and his wife were sentenced to six years of Yakut exile in 1902.

Aleksandra Brushtein first portrayed her teacher in the preface to her play Blue and Pink (1939) under the name of Mark Isaevich.

The admission of Jews to gymnasiums was strictly limited to a percentage: 10% in , 5% - outside the Pale, and 3% - in St. Petersburg and Moscow. This was also when the practice of "double" examinations emerged. In the early 1890s, open anti-Semitism grew stronger in schools. On May 8, 1894, the Vilna Herald published an article titled Action against the Inflow of Jews in Gymnasiums: "According to the Ministry of the People's Enlightenment, 10% of the total number of students in female gymnasiums are Jews in the entire population of all the gymnasiums. These numbers break down by school districts: over 11% in Kyiv, around 15% in Warsaw, and over 40% in Odesa".

Sasha's parents debated a lot over whether to send the girl to a girl's gymnasium or the Institute (its real name was the Mariinsky Institute for Women). Sasha's mother thought that there were many "girls like Sasha” in a gymnasium, so she would be better off there. But one can also think of another reason why Sasha was sent to an institute: gymnasium exams started later (so, in 1894, admissions exams to the Institute were held from 9 to 12 August, whereas at the gymnasium, it was on the 15th August), so the latter could well have been a backup plan in case Sasha wasn't accepted to the Institute. Even excellent examination results did not guarantee Jews admission: for example, Boris Pasternak, who passed his Gymnasium 5 examinations with flying colors in 1900, was not admitted because of the percentage limit (10 Jews for 345 pupils).

In describing certain events in the trilogy, Brushtein often points out that now, in the Soviet Union, there is nothing of the sort, nor can there be. The exam episode provides no such remarks, which is unsurprising - the first book of the trilogy was written only a few years after rampant Soviet anti-Semitic campaigns - "The Doctors' Affair" and "the anti-cosmopolitan campaign" were raging. The Road… is imbued with memories of the pre-revolutionary era and the very recent past.

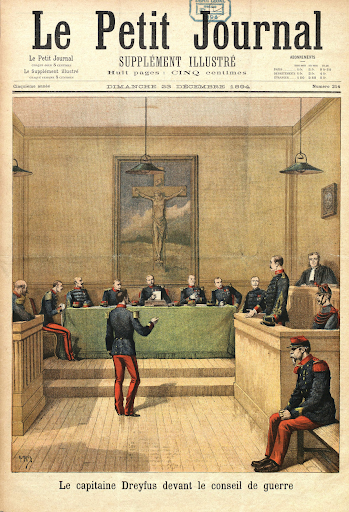

The Dreyfus Affair

by Henry Mayer from Le Petit Journal, 1894.

/ Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia

The Dreyfus trial was one of the highest-profile political events of the turn of the century. Alfred Dreyfus, a French general staff officer of Jewish extraction, was charged with espionage in 1894 because his handwriting was similar to that of a letter (bordereau) containing a list of secret documents. He was publicly stripped of his rank and exiled to Devil's Island in French Guiana. In 1895, the Dreyfus case was reopened, and in 1896, Colonel Picard identified the actual author of the bordereau as Major Esterhazy. In 1898, writer Emile Zola issued an open letter: I accuse. In 1899, the case was referred to the Court of Cassation, and the cruiser Sfax was sent to retrieve Dreyfus. In the trilogy, Aleksandr Stepanovich Vetlugin (his prototype is still unknown, but most likely, it is someone from the revolutionary Bund) explains the Dreyfus affair. Indeed, since early May 1899, Russian national and local newspapers routinely reported on the Dreyfus affair in foreign affairs sections; some cable dispatches about the matter occupied nearly half the newspaper's front page. However, only two years later, the details of Dreyfus's stay on Devil's Island became known when his book, Five Years of My Life, was published in Scientific Review and then as a separate edition.

Aleksandra Brushtein's archives contain numerous notes on the Dreyfus affair in Russian and in French: a handwritten copy of Zola's letter I Accuse, excerpts from Dreyfus' book Five Years of My Life, characterizations of Mercier, Picard, and Esterhazy.Brushtein's notes emphasize two things more than the trilogy does: how fast the conspiracy is weaving against the "spy" Dreyfus and its anti-Semitic dimension, reflecting the inevitable parallels between the Dreyfus affair and the many trials of the recent Stalinist era. Possibly while working on the third part of the trilogy, A.J. Brushtein was thinking of writing a play about Dreyfus. Among her notes was the scene of Dreyfus' arrest with a description of the setting and remarks by Dreyfus and Du Paty, the officer in charge of the preliminary investigation of the Dreyfus case and the graphological expertise. The writer's determination to tell the story of this trial, virtually forgotten by the time the trilogy was written, is by no means coincidental. The Dreyfus Affair was a momentous event discussed incessantly by Jewish intellectuals. To a large extent, it shaped the value system of the generation and social circle Aleksandra Brushtein belonged to.