Course

The Birth of Hollywood

In the Shadow of World War II: Émigré Noir

The Birth of Hollywood

Hollywood and Jewish émigré actors’

.

From People on Sunday Towards the Noir

Frame from the film People on Sunday. Directed by Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer,

and others, 1930. (Photo courtesy of https://seance.ru/articles/people-on-sunday/)

Noir went down in cinematic history as a movement, a genre and a style. Crime stories, femme Fatales, heavy shadows in the frame, rain and fog conjuring a dreamlike atmosphere are essential ingredients of film noir. The origins of noir are traced back to the American hard-boiled detective. Usually, two films by American directors, John Huston's The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Orson Welles' Touch of Evil (1956) are referred to as its beginning and end, respectively. Jewish filmmakers escaping Hitler's rule in Europe had pushed noir’s visual aesthetic to the limit and created most of its programmatic films.

It so happened that the vibrant gang that made the 1930 silent film masterpiece People on Sunday formed the backbone of the future leaders of the noir film movement. Billy Wilder and Fred Zinnemann wrote its screenplay. It was directed by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer, with Eugen Schüfftan as the cinematographer. Schüfftan later contributed to the 1937 film Port of Shadows (Le Quai des brumes) by Marcel Carné, a work of French poetic realism which in many ways determined the future noir). It was the last German silent film, an upbeat film that unfolded on the streets of Berlin, with the characters basking in their youth and enjoying life.

In Germany between 1930 and 1932, there were many upbeat films. With the advent of sound, this niche was occupied mainly by musical comedies, poorly preserved and somewhat forgotten by history. In contrast, People on Sunday persisted: brimming with light and air, it was the last breath of freedom before the world was thrown into the chaos of Nazism and World War II. There will be neither light nor air in the 1940s noir films: their characters and world will be trapped inside the confines of sound stage props and light-and-shade arabesques.

Double Indemnity

Frame from the film 'Double Indemnity.' Directed by Billy Wilder, 1944 (Photo courtesy

of https://lwlies.com/articles/barbara-stanwyck-performance-double-indemnity/)

Double Indemnity, on par with The Maltese Falcon, became a landmark noir film. Billy Wilder directed the film. Following People on Sunday, Wilder continued working as a screenwriter. Originally from a family of Polish Jews, he landed a job as a journalist in Vienna and later in Berlin, where he first began writing scripts. The day after the Reichstag fire, Wilder packed a single suitcase, took some money and a few original Lautrec posters, and headed for Paris. There, Wilder first tried directing on Bad Seed, which failed, and for lack of further prospects, Wilder left. Then, in the same year, 1933, he arrived in Hollywood.

His breakthrough comes six years later - Wilder writes the screenplay for Ninotchka by Ernst Lubitsch, his idol and mentor. Like Lubitsch before him, Wilder was to become a comedy maestro. However, it wasn't until the mid-1950s that he directed legendary films like The Seven Year Itch and Some Like It Hot, both starring Marilyn Monroe. At this point, however, Wilder wrote a few more successful screenplays, and finally, in 1944, he was given the go-ahead to direct Double Indemnity. Together with Raymond Chandler, they adapted the eponymous novel by James M. Cain for the screen.

The film has all the hallmarks of a noir: the plot is about an insurance salesman (reminiscent of a private detective) who gets caught up in a deadly affair orchestrated by a femme fatale named Phyllis. As it was to become commonplace in noir films, the on-screen action is accompanied by a voiceover, and the plot unfolds via flashbacks. The film is full of shadows and darkness. It becomes increasingly apparent that these shadows were not exclusively the product of the dreadful 1940s but also the roaring 1920s when German Expressionism was on the rise. As once in expressionist paintings, shadows harbored the protagonists' worst nightmares; in Double Indemnity, too, death stares at the protagonist through the dark lenses of Phyllis's sunglasses.

Sunset Boulevard

Frame from the film '\Sunset Boulevard. Directed by Billy Wilder, 1950.

(Photo courtesy of https://www.filmarchiv.at/program/film/sunset-boulevard/)

In 1950, Sunset Boulevard was released, crafted from Wilder's original screenplay, which would subsequently earn him and his long-term partner, Charles Brackett, an Academy Award. Once more, it is narrated through flashbacks, with a voiceover narrator, and it's a bleak and unforgiving tale of a faded film diva. Wilder here does something unheard of in Hollywood: rather than telling a story of a professional collapse or triumph, as in A Star Is Born, he makes a film noir about the life of a Hollywood star. Moreover, Wilder also uses the performers' real-life backgrounds when delivering the screenplay fiction. The entire lead cast of the film are legends of silent Hollywood: Gloria Swanson (starring as Norma Desmond), Buster Keaton (one of her guests), Erich von Stroheim (former director and now Norma's butler), director Cecil Blount DeMille ( playing himself). It's not just the film's protagonist that's fading away; it's also an era.

There is considerable sentiment in the film, but even more ghostly images of the dead. Norma Desmond's lavish home is a true Nosferatu's castle, where the living are not allowed to enter (hence the reporter and Norma's young lover's death). When Wilder was asked in an interview in 1975 about the expressionist imagery, his émigré experience and what it was like for him to be a Jew during World War II and how much of this came through in his screenplays and films, he just shrugged. He has no idea. Except maybe subconsciously, he does. And given how intimately expressionism and noir engage with that very fabric of the subconscious, that's no small thing.

Detour

Frame from the film 'Detour.' Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, 1945(Photo courtesy of

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6257-some-detours-to-detour)

Another outstanding film, the 1945 classic film noir Detour, was directed by Edgar Georg Ulmer. Originally from the Czech town of Olomouc, Ulmer was born in Austria-Hungary. Like Wilder, he moved to Vienna and there became a set designer at the Max Reinhardt Theatre. He worked with Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, directed People on Sunday and then moved to the USA. He had a successful career start at Universal. But one wrong move, having an affair and then marrying Shirley Kassler, the then wife of producer Max Alexander, a nephew of the head of Universal, Carl Laemmle, got Ulmer kicked out of Hollywood. Undeterred, he and his beloved wife left for the east coast.

In New York, Ulmer takes a job with one of the smallest and poorest B-movie companies, PRC (Producers Releasing Corporation), and puts the company's name on the map, acting as both a director and a producer. Ulmer is known for his ability to produce films quickly, cheaply and with high quality. " He shot Detour in just six days. This noir begins on the road, with the future narrator arriving in Reno and a guy by the name of Al getting off a car, entering a roadside cafe and there sinking in his thoughts of his recent past, his story. The familiar noir voice-over accompanies the scenes passing before Al's eyes. He is on the road again, catching a ride, but he is caught up in some bizarre events: the car's owner dies, and a mysterious woman approaches Al and starts blackmailing him. One more femme fatale and one more relentless shadow is looming over him.

Casablanca

Humphrey Bogart. Photograph from The Minneapolis Tribune magazine, 1940 / Wikimedia

(photo courtesy of https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/casablanca-film-mit-humphrey-bogart-und-ingrid-bergman-a-1170512.html)

Michael Curtiz and his 1942 classic film noir, Casablanca, is another celebrated émigré from Eastern Europe. Curtiz was a Jew from Budapest who had emigrated to the States in the mid-1920s at the invitation of Warner Bros. His 1942 release of Casablanca was a hit. It is not pure noir, more of a mixture of a spy movie and a romantic melodrama, made in a “dark" style. However, the lead actor in the film did come from noir - it was Humphrey Bogart, who had starred in The Maltese Falcon.

Casablanca is a transit point for those fleeing the Nazi regime. Among the supporting characters, one can indeed spot yesterday's refugees. Paul Henreid plays Laszlo, the leader of the Czech resistance movement. The Nazis did not care about Henreid's Jewish background - his father, a Viennese banker, converted to Catholicism in 1904 and changed his last name from Hirsch to Henreid. However, with his anti-Nazi remarks, Henreid earned the title of an enemy of the Third Reich. Henreid arrives in the States from the UK, where he is assisted in the emigration process by Conrad Veidt, the 1920s German star who played the sleepwalker Cesare in the first expressionist film, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari.

Veidt was cast in Casablanca as the German Major Strasser. Veidt flees Germany with his Jewish wife Ilona (originally from Miskolc). When the largest German studio UFA conducted a poll - everyone was required to fill out a form and specify their racial identity - out of solidarity, Veidt stated that he was a Jew. Another émigré star, Peter Lorre, also stars in the film, and Casablanca will prove to be not only a hit but also an émigré anthem. Most of the crew, starting with the director, are non-natives. And this, too, is very much of a noir narrative: no safe space in a world that is no longer home, with nothing left but unsettling sounds, smells, shadows and blissful forgetfulness, ever interrupted by flashbacks that keep catching up with you.

Sorry, Wrong Number

Frame from the film Sorry, Wrong Number. Directed by Anatole Litvak, 1948

(photo courtesy of https://mubi.com/de/films/sorry-wrong-number)

There are, in fact, some highly experimental noir films that come close in their innovation to Hitchcock's Rope, shot entirely in one space with very few cuts. One of them is Sorry, Wrong Number, by Anatole Litvak. Like Curtiz, Litvak had not been a part of Sunday People but had a similar background as an immigrant. Born in Kyiv, he fled to Germany in the 1920s following the revolution and then to France after 1933. After his film Mayerling (1936) had international success, he left for the States.

Paris was his favorite filming location; perhaps this was why in 1947, he directed The Long Night, a remake of the French film Le jour se lève (1939) by Marcel Carné. Or perhaps it was a coincidence that helped prove the link between the noir and the poetic realism that Carné's film exemplified. Either way, the remake, like the original, had the distinctive trait of having the plot unfold within only one space: the protagonist commits a murder and then barricades himself in his room. The viewers are told his story, leading up to the murder, through a series of flashbacks. Carné had a more interesting way of working with the objects in the room surrounding the protagonist than Litvack. But already in his next film, Sorry, Wrong Number Litvak proved that he too was no stranger to formal invention.

The lead female character, played by noir star Barbara Stanwyck (who featured in both Wilder's Double Indemnity and Siodmak's noir The File on Thelma Jordon), is trapped in her room. She is unwell. All she can do is make and answer phone calls. Through her conversations, she learns what has happened to her disappeared husband and the meaning of an inadvertently overheard conversation about an imminent murder. Litvak openly plays with the voice-over ever present in noir, shifting it within the frame through phone conversations. This noir has few visual subtleties, yet the sheer brutality of fate and the stifling tightness of the enclosed space are palpable.

Laura

Frame from the film Laura. Directed by Otto Preminger, 1944

(photo courtesy of https://www.moviebreak.de/film/laura)

Otto Preminger was born in Vyzhnytsia ( present-day Ukraine), where his family had fled after the Russian army had occupied the region in 1914. His father, Markus Preminger, secures employment as a prosecutor in Graz, and just one year later he is offered a higher office in Vienna should he convert to Catholicism. The father declines but moves to Vienna with the whole family anyway.

Two decades later, in 1934, his son Otto found himself in a similar situation: he was offered the position of manager of the Vienna State Theatre on the condition that he converted to Catholicism. Like his father, Otto refuses. Not a religious man, he still has no intention of betraying his roots. In Vienna, he works at the Max Reinhardt Theatre simultaneously with Ulmer. In the spring of 1935, Preminger accepted an offer from Joseph Schenck and left for Hollywood in October. His parents never accepted him leaving Vienna, and when he persistently tried to persuade them to move to the States, they would refuse to leave their city and country. Like Wilder's mother and grandmother, they were to perish in concentration camps.

The 1944 film noir Laura was Preminger's first major American success. The plot followed a police detective investigating the murder case of Laura Hunt. Imagine his astonishment when the allegedly murdered woman showed up at her flat safe and sound! The logic of the action - a string of suspects, interviews, evidence and the room where the murder took place - had the feel of an intellectual rather than a hard-boiled detective. Nonetheless, a certain amount of cynicism and noir means of expression were also present. The film became a classic in the genre, and Preminger went on to direct five more noir films in the following nine years. Finally, by the mid-1950s, Preminger amassed the means to start making independent films and tackle taboo subjects like pregnancy outside marriage, drug abuse and homosexuality. Gradually noir shadows, understatement and anxieties take on more specific plot outlines, and the noir era draws to a close.

Hard-boiled detective is a detective sub-genre that gained popularity in the United States during the Prohibition era. The lead character was usually a private investigator fighting against corruption and organized crime. The hard-boiled detective was remarkable for its high degree of cynicism resulting from the sheer brutality of the world around. Among the masters of the genre were Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, on whose novels many film noirs were based.

Poetic Realism was an artistic movement of French cinema in the 1930s that had a working class man as protagonist, and expressive means aiming at the poetization of his image. Prominent representatives were the poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert, and the directors Jean Renoir, Jacques Feyder, Marcel Carné and others.

Expressionist cinema was an artistic movement in German cinema of the 1920s characterized by grotesque distortions of space, contrasting light and a profusion of dark fantastical characters including vampires, golems, devils, ghosts and even personifications of death. Prominent representatives of this movement were F.W. Murnau, F. Lang, R. Wiene, P. Leni and others.

B-films are low-budget commercial films. Between the late 1910s and the 1960s, in the so-called "Golden Age" of Hollywood, these were films that were screened as number two in the theater during double feature screenings (hence the letter "B", like on a vinyl single record the second side is labeled "B-side"). Over time, the term came to denote any film with a low budget and often of poor artistic quality.

Introduction

The first permanent studio in Hollywood, "Nestor." Photograph by Witzel Studios,

1913. / Wikimedia

In the early 1900s, Hollywood as we know it did not yet exist, but there were plenty of immigrants in the States. People fled from poverty and . About two and a half million Jews immigrated to the US between 1880 and 1924. Most of them - over 90% - were from Eastern Europe. There were places for them to go. The number of working hours per week was slowly but steadily decreasing at the factories: some immigrant workers were gaining more time off, while others got a chance to keep them entertained. It goes without saying how important movies are to the entertainment industry. No longer a fairground curiosity as at the turn of the century, movie-going was gradually becoming a new habit. Across the East Coast - primarily in New York and Chicago - there emerge a plethora of nickelodeons (so named for their 5-cent admission fee, or 'nickel’). There were fewer and fewer newsreels in the program, and increasingly more feature stories. There was considerable profit to be made out of these ventures; with so many spectators passing through the halls the costs were recovered by a factor of tens or hundreds. The cinema in the 1900s transcended its role as mere entertainment, emerging as a profitable entrepreneurial endeavor. Transitioning from overseeing a haberdashery or drugstore to owning a movie theater presented a viable route to financial prosperity. This was a young industry, geared towards the young. Indeed, those who were the first to rush to the movies were individuals who, just a short time ago as teenagers aged 12, 15, or 16, had arrived with their families at the docks of New York. Today, they have amassed their initial start-up capital.

By 1907, the tide of emigration was at its peak, with more than a million foreigners from Europe (mostly South and East) arriving in the United States. Judging by Henrietta Sold's records, the Jewish population in America by this time stood at 1,777,185 (with 850,000 of them residing in New York City).

In the same year 1907 new developments took place in T. A. Edison's never-ending litigation against the use of his patented devices by other companies. The so-called War of Patents had been going on since 1897. However, a decade later, Edison suffered his first loss against AM&B (American Mutoscope & Biograph), his main competitor, and finally decided to merge. In December 1908, Edison and AM&B started the MPPC (Motion Picture Patent Company) casting a shadow of oligopoly looming over the budding film industry.

The MPPC then controlled all three stages of film production: the making of the film, its distribution and screening. Only those who had paid their share for using proprietary equipment can produce films. Only firms licensed by the MPPC could release films. Moreover, those who wanted to distribute films made by members of the MPPC (which now included half a dozen leading companies besides Edison and AM&B) had to pay a weekly tax. Furthermore, Kodak agreed to sell film exclusively to MPPC members (in return they would only use Kodak film).

Against this bleak background, the Trust's investigators prowled looking for any and all stolen technology and smashing up studio equipment, to say nothing of their clashes with the crew members. Consequently, people began to grow disgruntled one by one. At first, they tried to dodge the harassment and relocate to the west coast, to California, where it was not only safer, but also shooting conditions were much better - sunshine all year round. Eventually, having somewhat consolidated, the discontented turn into independents and give a proper fight back. As early as by 1915 the MPPC could forget about its former glory: by that time the Trust not only lost its patent rights to the Latham loop (the mechanism was used all over the place and eventually was made universally available regardless of the Trust's claims), but also found itself charged by the State with creating unfair trade conditions. Then came the time for the future Hollywood giants to rise. All of them - Louis B. Mayer, Adolph Zukor and a dozen other industrious immigrants - started off in the unruly 1900s with their own movie theaters. They then moved to Hollywood and by the mid 1920s, had set up the Hollywood film industry for the next half-century.

Paramount and Adolph Zukor

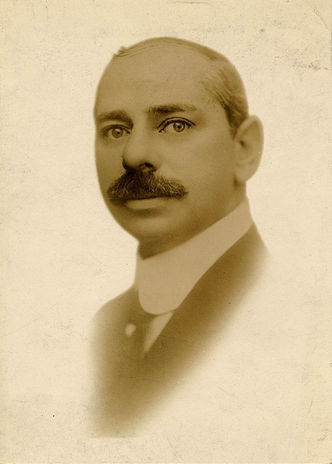

Adolph Zukor. Photograph by

Bain News Service, 1900. / Wikimedia

Paramount would become one of the first Hollywood majors discovering a new way to take control over all three production stages and to implement a block-booking system whereby cinemas will have to buy out and distribute the company's films in batches, with no option for individual film purchases. Nevertheless, Paramount would in many ways suffer the same fate as MPPC, appearing as a defendant in the 1948 U.S. v. Paramount case. This lawsuit would seriously disrupt the Hollywood system and clear the way for a New Hollywood, with new independent companies for the production, distribution and theater release of films. But in the meantime, the future leader of the company, Adolph Zukor, was just starting out on his journey.

A native of Ricse, a in Hungary, Adolf with his older brother Arthur had lost his father at an and when Arthur goes off to study in Berlin, Adolph is just turning 15. The world is buzzing around him. Ever more often and more appealingly, there are stories from the people who have emigrated to the States. As Arthur departed for studies in Berlin, a 15-year-old Adolph became immersed in a world vibrating with enticing stories from those who had ventured to the States. So Zukor decided to make the trip. He was still underage, so he passed an interview with an agency in charge of providing money for orphans. They sent the required amount of money to his brother in Berlin, and the latter sent Adolf on a ship to Hamburg. So with $40 sewn into his belt, Zukor set sail to New York.

Zukor started working in a fur store, showed great results quickly, saved up and opened his own movie theater. However, it was not called Nickelodeon - Zukor charged twice as much for entrance, 10 cents - instead it was called Comedy Theater. His intuition did not fail him. He sat in the movie screening after screening, observing the audience's reaction, and then decided to take on the expensive release of "Queen Elisabeth" with Sarah Bernhardt.This presented a gamble: the film was extraordinarily lengthy for its era, reaching over 40 minutes across four parts, and additionally, Zukor intended to establish a lofty price for featuring the renowned actress.The plan worked out. Zukor proceeded on to produce his own films, applying the success formula: cast famous actors in famous plays. Mary Pickford became his first star. At the time, Paramount was the biggest distributor. Zukor, who in addition to active production independently managed more than a hundred movie theaters, distributed his films through Paramount as well. Now was the time to consolidate: to shoot, distribute, and screen under one roof. So Zukor did just that, purchasing a seat in Paramount's management and turning the distributor firm into a major studio.

Marcus Loew and brothers Nicholas and Joseph Schenck

Markus Loew. Photographer unknown,

1914. / Wikimedia

Marcus Loew was instrumental to the birth of the legendary Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) film company. He was born in New York City, in a poor Jewish family. His father had emigrated to the United States from Vienna. Loew began working when he was six years old, as a newspaper boy. He was in his thirties when he decided to become an entrepreneur. It was Zukor who encouraged him and guided his efforts. The business thrived and by 1911, he owned about 400 movie theaters across the country; he also hired the Schenck brothers. The brothers, alongside their family, immigrated to the U.S. in 1892 from Rybinsk. At the time the elder Joseph (Osip) was 16 and the younger Nicholas - 12. These two also sold newspapers, ran deliveries, and studied chemist's trade in the evenings. Before joining forces with Loew, they had opened several drugstores. Joseph Schenck took off for California in 1916 and went on to have a career at United Artists and later at Twentieth Century Pictures. Nicholas, the younger of the two, stayed with Loew, and after he died in 1927, took over and ran MGM until 1955, when Loew's son Arthur took over as president.

The MGM company was founded in 1924: Loew had first founded the Metro Company, which was to handle distribution in addition to the film network. However, Loew's ambitions expanded beyond distribution and screening, propelling him into film production. Yet he still needed skilled professionals. So he brought two producers, Louis B. Mayer and Samuel Goldwyn, into Metro's operations. The work was done and another Hollywood giant was born. Mayer loathed Schenck and called him "Skunk" behind his back, while Goldwyn would never be involved with MGM since Metro, leaving behind nothing but the "G" in the company's name. Regardless of their differences, these brilliant businessmen not only came from similar backgrounds, each also contributed to creating Hollywood's great past.

Goldwyn-Mayer

Louis B. Mayer. Photographer unknown,

1919. / Wikimedia

Louis B. Mayer, or Lazar Mayer, was originally from either near Minsk or from the village of Dymer (now Kyiv region), his parents had emigrated fleeing the pogroms when Lazar was two. His exact date of birth is unknown, but it is believed to be around July 12, 1884. Nevertheless, Mayer, upon obtaining citizenship, chose July 4, U.S. Independence Day, and later adjusted the year to 1885. Of all the Jewish immigrants, he was perhaps most eager not just to assimilate, but rather to blend in to his new homeland. Not only did he alter the date of his birth, he also celebrated Christmas, arranged special games of egg searching at Easter in his house, and he had a portrait of Cardinal Spellman on his desk in his office. Meyer began much like everyone else by setting up a movie theater in Haverhill, scraping together money for rent from family and friends.

Goldwyn's situation was somewhat different: he had made a fortune in the glove industry before venturing into films. Samuel Goldwyn, or Shmuel Gelbfish, came from Warsaw. Upon his father's death, he went to live with relatives in Hamburg, where he was trained as a glove maker. Subsequently, via England, he migrated to the States in 1899. With his skills, he quickly ascended to a managerial position at an elite glove company, then to vice president. In 1913, Goldwyn, together with his brother-in-law Jesse L. Lasky established a film production company. Sometime later, in 1916, Lasky forged a partnership with Zukor forming the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, which would simply become known as Paramount. Samuel Goldfish, having adopted that surname during his time in England, stayed with the company, but after several confrontations with Zukor he decided to leave. In that same year, 1916, in partnership with two Broadway producers, Edgar and Archibald Selwyns, he started the Goldwyn Pictures Company. Hence the Goldwyn name: first, Samuel Goldfish combines parts of the surnames - Gold+wyn - and then, in 1918, he also changed his last name to Goldwyn. Once part of both Paramount and MGM, Goldwyn was by no means driven by the idea of manic control over the three stages of filmmaking, he remained independent, famed for his ability to scout talent and kept making movies at his company, Samuel Goldwyn Pictures, up until 1959.

1933 - Point of No Return

Al Johnson as Cantor Rabinowitz. A still from The Jazz Singer,

directed by Alan Crosland, Warner Bros. 1927 г.

Since 1933, when Hitler came to power and the National Socialists became the ruling party in Germany, hundreds of first-class European actors made their way to the streets of Los Angeles and Hollywood studios. Some went straight to Hollywood from Germany; others first fled to Austria, France or even the USSR. Those were people dissenting from the regime, those seeking shelter from the war, but first and foremost, naturally, the Jews - more than five thousand arrived in Los Angeles between 1933 and 1945. One would think there would be plenty of room for everyone in America's , but this was not the case. While language and accent were of secondary importance to the camerapersons, filmmakers, or screenwriters, they were vital for the actors. The new Hollywood policies seem to have further complicated the situation. Throughout the 1930s, the major studios strived to produce onscreen characters as neutral as possible, devoid of national peculiarities in speech and appearance. This particularly affected Jews. Jewish characters vanished from the screen, and Jewish last names disappeared from the credits.

This shift occurred for several reasons. First, the sound enters the film, and along with it comes the requirement of standard American accent (yet the sound era in Hollywood started with a Jewish boy: Jakie Rabinowitz, in The Jazz Singer). Then, centred on Catholic family and morality came into full force from 1934 onwards. The aforementioned "melting pot" concept also plays its part, as the screen characters trying so hard to blend into the mainstream of American society lose all ethnic identity. Foreign politics were also involved: the studios were determined to remain neutral. Since Germany was a significant market, films were also made to suit the tastes of local audiences (i.e. the local government). When two hundred and fifty Jewish actors arrived in Hollywood with their vast theatrical experience and strong German accents, very few roles could be offered to them, for they were all too different. Except maybe the characters who were different as well.

Peter Lorre - Lang's child-killer maniac

Peter Lorre as Rodion Raskolnikov. Crime and Punishment,

directed by Joseph von Sternberg, Columbia Film, 1935.

Peter Lorre certainly is one of the most famous immigrants of the 1930s and 1940s. A native of Ružomberok (today's Slovakia), he arrived in the US with substantial professional experience. He became a household name in 1931 after playing the role of a child killer in Fritz Lang's M. But even back then, at the time of filming, Lorre had the time to try himself in Jacob psycho-theatre. That was his escape from his studies in banking. He had also worked with Bertolt Brecht. (Both Brecht and Lang also immigrated to the USA, Moreno moved there as early as the late 1920s). So by the time director Josef von Sternberg called Lorre for the lead role in Crime and Punishment in 1935, the actor had already developed his own recognisable style of acting.

The chubby face, the enormous eyes, either mournful or insane, the soft, quiet voice - none of these betrays the brutality of which Lorre's characters are usually capable. The effect of the hypnosis, under which the character appears to be subjected to, nearly always plays a decisive role in the plot. Nearly always, he is led, helpless, and ill. It is precisely with this bunch of characteristics that Lorre lands first the role of Raskolnikov (later, the film will be described as a vulgar adaptation of Dostoevsky′s novel, in which Lorre is perhaps the only reminder of the original work), and then a dozen other films. He played mad professors, murderers, and petty crooks and always retained this otherness, this eccentricity in his characters. Despite becoming the lead actor, Lorre was far from being the only eccentric Jew on the screen.

Eccentrics in supporting roles

Vladimir Sokolov (right) as Anselm. For Whom the Bell Tolls,

directed by Sam Wood, Paramount Pictures, 1943.

Lorre's popularity derives from the fact that he had started his Hollywood career with leading roles, but this was something of an exception. It was much more common for Jewish actors to play strong supporting roles. Luckily many used to play such roles before emigration. Yet at German and Austrian studios, unlike in the US, most actors had theatre training - actors would come from the companies of Max Reinhardt, Brecht, Tairov or even Terevsat (Theater of Revolutionary Satire). These differences in professional backgrounds meant that their acting was also different. Theatre actors would always introduce an element of eccentricity into their character: they would not just put on an exaggerated moustache or a voice but would alter their manner of acting altogether. Sometimes it was the clumsiness of movements, whereas at other times, conversely, a melodic, smooth manner of speech and movement. Thus, many unhinged eccentrics made their way into Hollywood films of the 1930s and 1940s.

These were not just waiters, accountants and comedians. If Jews could not play Jews, they had to play persons of all ethnicities. Vladimir Sokoloff beat all records in this. Originally from Moscow, he first played at the Khudozhestvenny Theatre, then at the Chamber Theatre with Tairov, and finally with Reinhardt. At the invitation of the latter, Sokoloff stayed in Germany. In 1932 he moved to France, and from there, in 1937 - to the United States. In Hollywood, Sokoloff played about a dozen different ethnicities in dozens of films: in West of Shanghai, he played General Chow Fu-Shan. In an adaptation of Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls, he played a Spaniard, Anselmo. In Emile Zola he played Paul Cézanne. And, of course, he also played a plethora of Russian characters - ranging from the smuggler Dimitri in Alaska to Kalinin in Moscow.

More than just a Russian - a Communist

Mikhail Razumny (left) as an officer. “Comrade X”,

directed by King Vidor, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1940.

In 1939 and 1940, two films of very similar subject matter were released, making possible another comic persona that seemed to be tailor-made for Jewish émigré actors. Not merely a Russian - a communist. First came Ernst Lubitsch's Ninotchka. The story is about three Soviet envoys dispatched to Paris to sell off valuables looted during the revolution. The three cannot resist the temptations of the bourgeois lifestyle, so Nina, a Party official, is sent to their rescue. The sparkling Felix Bressart, a Jew from Eydtkuhnen (now Chernyshevskoye), played one of the envoys. He is joined in the trio by Sig Ruman, a long-time German émigré, and Alexander Granach, a more recent Jewish emigrant, referred to a little later.

The other film was “Comrade X”. This time, an American reporter, McKinley (Clark Gable), travels to the Soviet Union to write a series of scathing articles under a pen name “Comrade X”. He is quickly exposed by his manservant Vanya ( also played by Bressart). However, Vanya has a condition: he will not expose McKinley, only if he takes his daughter Theodore across the border to the States. After the US entered the war in 1941, becoming an ally of the USSR, Hollywood stalls the release (and re-releases) of anti-Soviet films, but the cinematic image lingers. Besides Bressart, “Comrade X” also features Sokoloff and Mikhail Rasumny (from Odessa). Like Sokoloff, Rasumny made it to Berlin right after the 1927 tour of the Khudozhestvenny. He had considerable experience not only as an actor but also as a theatre manager: in 1919, in Vitebsk, he founded the Terevsat (with Marc Chagall as the set designer), and in 1933, when he left Germany and moved to Paris, he founded the Jewish Theatre-Revue. And then, in 1938, in New York - the Jewish Drama Studio. In Hollywood, he would play anything: restaurant managers, mechanics, and ordinary Russians, and in For Whom the Bell Tolls, he played the , Raphael. The role of Theodora in “Comrade X” was played by Hedy Lamarr, who, like Lorre, was fortunate enough to become a full-fledged star in emigration.

The one and only Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr as Conductor Fedora. Comrade X,

directed by King Vidor, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1940.

Hedy Lamarr, or Eva Maria Kiesler at the time, began her career in her native Vienna, where her parents had met: Emil Kiesler, originally from Lviv, and her mother, Gertrud, from Budapest. Hedy Kiesler calls on Reinhardt, meets him and even plays with Lorre (in 1931 The Trunks of Mr O.F. by Alexis Granowsky). In 1937, she secretly ran away from her husband Fritz Mandl with a handful of jewellery in her hands and a firm determination to sign a contract with MGM. The problem was that Kiesler had an accent and had previously played inappropriate roles. In 1933, she played in Gustav Machatý's Ecstasy, where not only did she appear naked in one scene, but she also acted out an on-screen orgasm (the first ever in film history). Under the strict Hays Code, which governed the entire Hollywood production, this was utterly unacceptable. And yet Kiesler had a powerful bargaining chip: she was a beauty. To Mayer, one of MGM's executives, that was good enough, so he came up with a screen name for her - Hedy Lamarr - and signed her up.

The film that started Lamarr's Hollywood career is very telling: it is the 1938 “Algiers” by John Cromwell, a French “Pépé le Moko” remake. This is a story about Casbah, a city neighbourhood that lures one into its web like a trap and never lets one go. The protagonist, Pepe, meets a mysterious woman (Lamarre) who stirs up memories of his beloved and unattainable Paris and makes him decide to leave Casbah. It ends tragically, with the foreign woman emerging as Fate's embodiment. Similar roles had also been reserved in Hollywood for earlier European immigrant divas - Garbo and Dietrich. They were to look foreign, enigmatic and fatal. However, Lamarr was too obviously beautiful, which stood in the way of mystery. Therefore, she wasn't entirely enshrined in this particular persona. Down the road, she had roles much like those of her other colleagues - a Viennese refugee ( “Come Live with Me” by Clarence Brown, 1941), a Chinese-French beauty ( “Lady of the Tropics”, Jack Conway, 1939), daughter of Hungarian artists (“Dishonored Lady”, Robert Stevenson, 1947), or the role of a Soviet streetcar conductor, as in “Comrade X”.

Confessions of a Nazi Spy

Heisler, Allied Artists Pictures Corporation, 1962 / Wikimedia

After Kristallnacht in 1938 and the following engagement of the US in the war in December 1941, several anti-Nazi and propaganda films were made (about 180 films between 1939 and 1946). With each new film, the German authorities banned further distribution of films by one company or another and closed down its local studio subsidiaries. Paramount was the last to withdraw from Germany in October 1940. Ironically, Hollywood urgently needed an immense number of actors with German accents who could play members of the SS, the Gestapo, soldiers, the Führer and his entourage. Finally, over 65% of the emigré actors found employment in film productions. Obviously, that included Jewish actors as well.

The first in the line was “Confessions of a Nazi Spy”, released in May 1939. And Warner Bros., who produced the film, were the first to close down their German branch immediately after the November . Francis Lederer played the lead spy in the film, he was born in Prague, where he attended the Academy of Dramatic Arts, and after World War I, he performed in German theatres, including that of Reinhardt. Lederer decided to stay in the States once he arrived there in 1933 on tour: it was no longer safe to return to Germany. His partner in the film, Lionel Royce, is another German spy but in a supporting role.

Royce was born in the Galician town of Dolyna (now Ivano-Frankivsk province, Ukraine), enlisted as a volunteer in WWI, promoted to lieutenant, and worked as an actor after the war in Vienna and Berlin. He first fled to Austria and from there to the USA in 1937.

Martin Kosleck (real name Nicolaie Yoshkin) played Goebbels in this film. Kosleck was born in Barkotzen (present-day Poland) in Pomerania into a Russian-German Jewish family. Trained by Reinhardt, he came to the US as early as 1932, but things didn't work for him in Hollywood. Kosleck returned to New York, where he went on acting before he was called by Anatole Litvak, the film's director, to play in “Confessions of a Nazi Spy”. Litvak himself had a similar trajectory: born in Kyiv to a family of Lithuanian Jews, he moved from the USSR to Germany, from there to France in 1933 and finally to the USA in 1937.

Jewish actor - top screen-nazi: Alexander Granach

Alexander Granach as Alois Gruber. Still from "The Executioners Die Too!"

directed by Fritz Lang, Arnold Pressburger Films, 1943 / Wikimedia.

Actors accepted their parts without any fuss - it was the job. They would only refuse parts in films if they thought they were too small for their status or if they feared being recognised in Germany or Austria, where they still had relatives - this was also a frequent reason for actors to have their names changed in film credits. Alexander Granakh ( a native of the village Werbowitz in the present-day Ivano-Frankivsk province of Ukraine) also played Nazis on more than one occasion. He had an acting background of his own: like Lorre, Granach had previously appeared in very expressive roles, not just the typical, but instead, he played in a unique individual manner.

In the 1920s, he famously played Knock, Nosferatu's manservant, in Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau's “Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror”, and Judas Iscariot in Robert Wiene's “I.N.R.I”. Granach decided to flee Germany for the USSR, but things didn't work out too well; he barely escaped prosecution on espionage charges (it was a miracle that a letter from Feuchtwanger was found among Granach's possessions during a house search). From the USSR, he went to Zurich, where he appeared in a couple of productions, and then he set off for the States.

He then played communists in Lubitsch's films and had a supporting role of a Pole in “So Ends Our Night”, a 1941 adaptation of Remarque's “Love thy Neighbour”. When anti-Nazi films took off, he switched to playing Gestapo types - in Robert Stevenson's “Joan of Paris” and Fritz Lang's “Hangmen Also Die!” (based on a screenplay by Brecht). Like Royce, Granach joined the army as a volunteer during WWI, was taken prisoner and escaped. There Goes a Mensch," which chronicles his extraordinary journey through small towns and major capitals, emphasising his zest for life. The book culminates in 1936 with his portrayal of Shylock, a role he had always aspired to play and eventually did at the Kyiv State Jewish Theatre. Sadly, another war loomed on the horizon.

Other courses

Jews in the Weimar Republic Cinema