Lviv: Multiculturalism Across the Ages

City on the Poltva

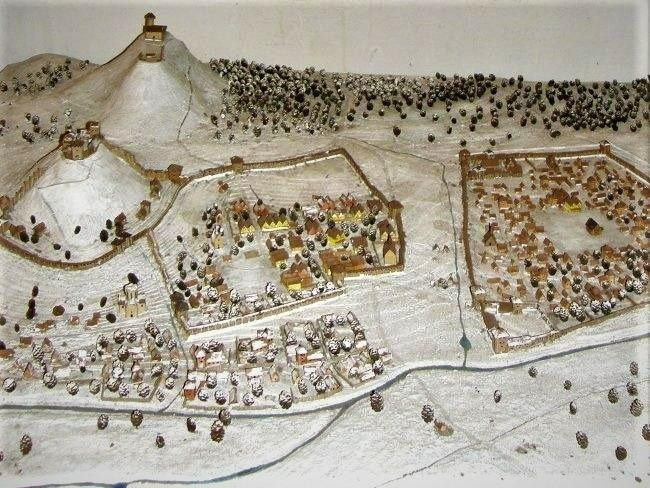

Panorama of princely Lviv. Layout in the dungeon of the Jesuit church.

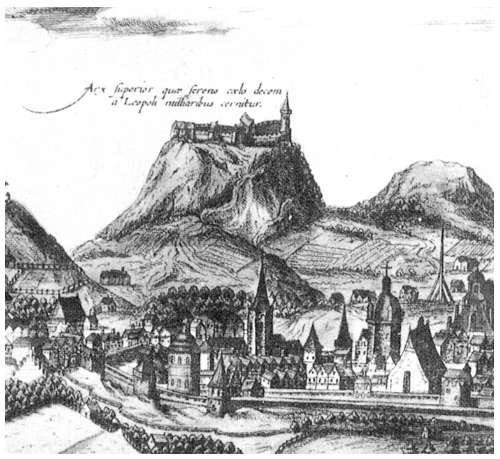

According to the most widely accepted version, Lviv was founded in mid the 13th century on the border of the forest and forest-steppe areas on the banks of the river Poltva, in a picturesque area full of water. The city, which was in the possession of Prince Daniil of Galicia, bears the name of his son Lev (who later also ruled in the Galicia–Volhynia Principality) and has kept it unchanged, regardless of the language: Lvov, Lviv, Lwów, Lemberg. In Latin the city’s name is Leopolis, or Civitas Leona, the Turks used to call it "Illi" or "Illibot", the Greeks "Leontopolis".

It is a classical medieval city — with a castle (which once stood on a mountain that today is called "High Castle"; no traces of it remain), castle outskirts ("Podzamche"), and a downtown area (commercial and craft areas) - Lviv was part of major European powers for most of its history: the Kingdom of Poland, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austrian Empire, and Austria-Hungary. From the 13th to the 20th centuries, these lands were a borderland of several states, which resulted in a multi-ethnic and multicultural make-up of the population, an interweaving of political, ethnic, religious, and social conflicts that turned the region into an unstable frontier.

Jewish Community

vov Jews led by a rabbi. A drawing in the margins of a document from the Lvov Magistrate, 1714. (History of the Jewish People in Russia, Vol. 1, p. 271).

Lviv’s population (another sign of a genuinely European city) has always been heterogeneous and was made up of the Polish, the German, the Armenian, Jewish and Tatar communities.

According to historian Dan Shapira, Jews first came to Galicia from the cities of Crimea and the Balkans at the same time when Lviv was founded, i.e in the 13th century. After the Mongol conquests, Turkic-speaking Karaites arrived in Galicia and Volhynia from the Black and Caspian Sea basins and from the Volga Bend and settled in Lutsk, Lviv and Galicia. Jews continued to immigrate in later periods as well, from Germany (Ashkenaz), Spain (Sefarad) and Italy. This brought about the multiculturalism within the Jewish community itself, where different traditions, customs, and cultural practices coexisted.

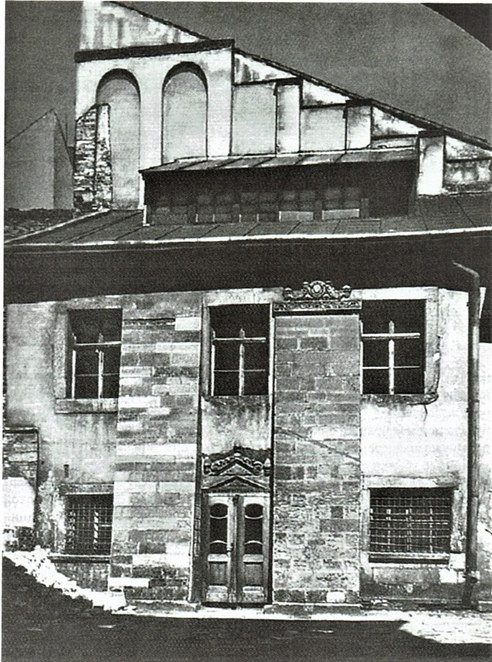

In the 13th century, the first Jewish community emerged in the southern part of the city. This oldest community later became known as the "suburban community," while another one emerged in the city center – the “urban” one. The community was located east of Castle Hill, between the latter and the banks of the Poltva river. Its main synagogue – the "Golden Rose '' – had an interesting fate. It was built at the end of the 16th century on the site of an old prayer house that had burnt down in a fire, with funding provided by a wealthy merchant Isaak Nachmanovitch. Having won a protracted fight with the Jesuits over the right to own the lot of land, the Jews were finally able to build the synagogue in 1603 at the cost of large payments to the city treasury. After Isaac's death, his daughter-in-law Rosa Nachmanovitch played a prominent role in the struggle for the right to pray in the main synagogue. Her memory was immortalized in the synagogue’s name, the Golden Rose. After 350 years, the synagogue was demolished by the Nazis in 1942, during the occupation of the city. Today one can still see some remaining fragments of the structure.

Golden Rose Synagogue (1582). Photo from the 1930s. (History of the Jewish People in Russia. Vol. 1. P. 275).

The names of some famous members of the medieval Lviv Jewry have been preserved: a merchant named Volchko, a royal factor granted with the right to collect taxes, a saltworks tenant; a physician called Shimon, who treated the king himself; one Israel Zlochevsky, a tenant of ponds, breweries and pastures, shops and mills owner. Widespread among the Jews of Lviv were such trades as goldsmiths, blacksmiths, and carpenters; Jews were also butchers, tailors, bakers, and skinners. Moreover, Lviv was a center of Jewish scholarship: it was home to Isaac Halevi, the author of Hebrew grammar, and his brother David, famous for his commentary on Yosef Karo’s Shulchan Aruch, the"Turei Zahav”.

The urban and the suburban communities had separate schools, synagogues, and mikvahs, and only the cemetery was shared. Unfortunately, the relations between the two communities were less than friendly. As Meir Balaban wrote, "A Jew from one community looked upon a Jew from the other with suspicion or contempt, suburban Jews generally referring to city Jews as fools, and the urban community members referring to suburban Jews as slobs and idlers”.

The two communities did not merge until the nineteenth century.

Rabbanites and Karaites

The Karaites came to Galicia together with the Tatars after the victory of the Lithuanian prince Algirdas over the Horde in 1362. Under Prince Vytautas they were relocated to Trakai, where they served as guards for the Lithuanian princes, and consequently were moved to Lutsk and Galich. There used to be a large Karaite settlement in Galich. Nonetheless, according to M. Balaban, the Karaite community of Lviv was the oldest in Galicia.

Despite The Karaites and the Rabbanites polemicizing on halakhic issues, this polemic only reinforced the Karaite self-identity and didn’t lead to neither alienation nor to hostility between the two communities, unlike the polemics between the Jews and the Christians. Smaller in numbers, Karaite communities led their lives competing with the Christians and the Rabbanites and, as recent research has made clear, their culture was shaped by the influence of studying Mishnah, Talmud, the Commentaries and Kabbalistic writings. What fostered this were the close bonds between the Karaite and Rabbanite communities, that had set the stage for contacts, exchange of literature and even for training of Karaites under Rabbanite teachers. It is known that in 1457 the Karaites community lived outside the city walls, and for 1414 there is evidence of a shared cemetery in Lviv, used by both Karaites and Rabbanites.

The widespread view that for centuries there was an impenetrable divide between the two communities is typical of nineteenth-century studies, still referred to today. In fact, until the end of the seventeenth century, there were no anti-Rabbanite trends in Karaite literature, and the Karaites self-identified as "we, the sect of the Karaites" within the larger community of the people of Israel.

Jews and Armenians

"Ruthenians, Armenians, and Jews lived in the suburbs and had their temples here, for their ancestors had settled here," wrote historian and theologian Józef Bartłomiej Zimorowic in his book Leopolis Triplex (Triple Lviv) in the second half of the 17th century.

Armenians and Jews have always lived in close proximity. According to official historiography Armenian settlers first appeared in the Galician land around 10th—11th centuries, starting their first settlement near the Castle Mountain, along one of the main trade routes of the period. At the end of the XII century the Achkatar monastery and the church of St. Anne were consecrated.

After Lviv had been annexed to the Polish Kingdom and the city had been granted Magdeburg Rights (1356), the medieval nucleus of Lviv started to emerge with the construction of a motte-and-bailey and fortress walls around it. Armenian settlers were allocated northern quarters of the city; and from the mid-14th century on the three Armenian streets (Upper, Lower and the Diagonal) as well as the entire Armenian Quarter started growing.

The Armenian street ran from the fortifications on one end to the Market Square on the other. Supposedly, Lviv’s Armenian community was the largest in Russia, because it was here that the Diocese of all Armenians of Rus and Wallachia. was founded in 1364. It can be claimed that the Armenian community in Lviv, as well as the Jewish community, stood at Lviv’s origins and took an active part in its development. Around that time (1356-1363) the Armenian cathedral was built. And in Podzamche, not far from the Old Market Square, two Armenian churches were built - St. Jacob (Surp Akop) and the Holy Cross (Surp Khach). After the new city was founded, Podzamche received the name of the Armenian Trade Quarter. Here, the Armenian river ran under the Armenian bridge, there were Armenian baths and houses there. Nowadays B. Khmelnitsky street runs through this area. The Old Market Square has survived, and out of four churches only one remains - the Armenian Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Jews and Authorities

Panorama of Lviv. XVII century engraving.

In 1367, King Casimir the Great reaffirmed the privileges held by Lviv’s Jews. Although their residence in the city was strictly limited to the Jewish quarter, within its limits they felt safe. Gradually, in the course of the general decentralization of power in the Polish-Lithuanian state, the dependence of the Jews on the feudal lords exacerbated, and from 1539 the local authorities were given full jurisdiction over them. That said, king’s protection often saved the Jews from major calamities. For instance, in 1576 the Jesuit monks of Lvov spread a rumor that the Jews had killed a Christian child for ritual purposes. An enraged mob began looting Jewish homes and killing Jews. The community sought help with the king. Despite the fact that Stephen Bathory's envoys found the accusations to be false, the rights of the Jews were restricted (for example, they were forbidden to sell meat at retail) just in case.

The Lviv community managed to bribe itself out of trouble and survive the terrible years of the Khmelnytsky Uprising.

Jews and German Culture

Since 1772 Galicia formed part of the Habsburg Empire. Maria Theresa's imperial system sought to contain the growth of the Jewish population and limit their economic activity: for instance, in Lviv, Jewish surgeons were banned from treating Christian patients, from engaging in barbering and gynecology. But already under Joseph II all restrictions were lifted, Jews received the right to engage in "all trades and arts," become land tenants, and the obligation to wear black coats and hats was abolished. Measures to put an end to the autonomy of the kahals and to conscript Jews into military service served the purpose of integrating Jews into German culture. The imperial authorities simultaneously expanded Jews’ rights and oppressed them in some respects: thus, in Lviv, Jews were allowed to live only in the area of the former ghetto and adjacent streets; this prohibition did not apply to the rich and those who held university degrees, but “foreign Jews" were not permitted to stay in Lviv. In the nineteenth century, the situation of Jews in the cities deteriorated, while in the countryside, where they lived on Polish landowners’ estates, it remained unchanged.

Austrian Galicia became one of the centers of the Jewish Enlightenment, the Haskala. Aaron Friedenthal founded a teachers' seminary in Lviv. Nachman Roshal and Shlomo Rappoport, philosophers and theologians, worked here. The adherents of Reformism Judaism emerged: Rabbi A. Kohn preached in German and edited a newspaper in the same language. Through his efforts a Jewish school was opened. The inhabitants of the suburbs, zealous adherents of Hasidism, remained followers of Rabies such as Sholom Rokach of Belz and Moshe Leib of Sasov. The orthodox trend was led by Rabbi Yakob Ornstein, an opponent of the Kohn,.

The Jews of Lviv took part in the revolution of 1848 on the side of Polish interests, fighting for which was then seen as a revolutionary democratic movement. From the revolution Jews expected to gain equality, civil and political rights. The Jews of Galicia supported the creation of the National Guard, which was supposed to safeguard constitutional reforms in the cities. Among the most active figures in the revolution were O. Horowitz, M. Mises, Rabbi A. Kohn.

After the defeat of the revolution, restrictions against Jews were reinstated, and special taxes were imposed. The city authorities of Lviv denied Jews civil equality. The governor, Count Gołuchowski, commanded: "The Jews of Lviv to remain within the walls of the ghetto”. Significant changes became possible only after the 1867 constitutional reform when the empire was transformed into a dual monarchy. Since then, political activity among the Jews is on the rise, with Jews becoming members of parliament, regional Sejm and magistrates (in Lviv there were 5 Jewish delegates in the regional and local authorities). Paradoxically, deprived of their rights of national unity, the Jews allied themselves with the Poles, and were used by them in their own interests, that is against the Ukrainian majority. This is what V. Zhabotinsky wrote about in 1906: "In the entire Polish hegemony in Galicia, the decisive role so far has been played by the help of the Jews. Fraudulent census “counted” all the Jews of the region as ethnic Poles, and the loss of this “increment” would mean the end of the legend of Polish majority ... Poles understand it better than anyone- hence the hatred with which they pursue Jewish “separatism”." Indeed, in 1900 more than 17% of the Jews of Galicia stated German as their spoken language, Polish was named by more than 76% and Ukrainian by 5%. It is quite telling that the real spoken language for most of them - Yiddish - was not recognized by the Austrian authorities and was not included in the census forms. Two-thirds of all Jews of Austria-Hungary lived in Galicia, and in Lviv they accounted for a quarter of the population.

Hasidim, Mitnagdim, and Maskilim

In early twentieth-century Lviv, the major tensions were not between Hasidim and Mitnagdim (or Misnagdim), but rather between the former two and the enlighteners, the Maskilim. The antagonism span across matters such as traditional dress, language, and secular education. L. von Sacher-Masoch, born in Lviv, wrote of his fellow Traditionalists: "An oriental character, knowing neither past nor future, living only in sensual modernity, a brilliant spirit, the same spirit of Solomon's wisdom and Talmudic wit, a bright and colorful phantasy". The conflict between the Hasidim and the Enlighteners led to the latter being banned from the local communities and cursed. Prominent enlighteners - Nachman Krohmal, Solomon Rappoport, Emmanuel Blumenfeld - founded a Reform synagogue, which was opened in 1844. In the 1860s the synagogue also became a place of non-religious gatherings of the Jewish public. Sermons were preached in German and after 1903 in Polish.

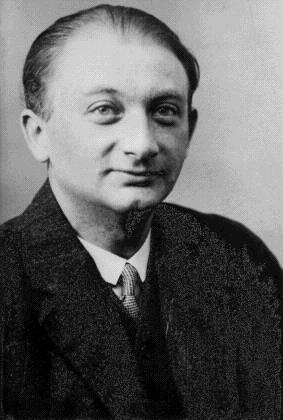

Interestingly, the tendency toward assimilation encompassed not only the political sympathies of a portion of the youth, but also the literary circles. A number of writers, although writing in Yiddish, were influenced by the Viennese bohemian atmosphere, and in their works one finds a large number of hebraisms. Others switched to Polish or German (Julian Tuwim, Bruno Schulz, Karl-Emil Franzos). They created the myth of Galicia as a supranational space. The work of Joseph Roth (1894-1939) a native of Brod, who spent his youth in Lviv and studied at the University of Lviv, is rightly seen as the peak of this myth. His novels describe the atmosphere of a primal "homeland," where Slavs, Germans, and Jews coexisted, and where languages, customs, and religions mingled. Real and imagined exoticism conferred upon Galicia the fame of being the "Wild West" of the Habsburg monarchy.

Jews between Poles and Ukrainians in The Second Polish Republic

The restoration of the Polish state in 1918 opens a new page in the relationship between its three largest ethnicities - Poles, Jews and Ukrainians. This relationship was always complicated. The strive to secure a mutual understanding with the dominant ethnicities, as well as the need to master the official language of the state, gave rise to new tendencies in Jewish society: a pull towards the dominant culture, double loyalty, and a desire for assimilation. Since the mid-1920s, there was a mass transition to the Polish language.

The Jews primarily belonged to the urban community, while the percentage of the rural Jewish population was insignificant. In this situation, the position of the Jews was complicated by the need for economic emancipation of the masses of the Ukrainian peasantry, of the petty bourgeoisie, and of the emerging middle class. The Jews had to stand their ground.

Attempts by Jews to reach separate agreements with the government, as the one in 1925, led to conflicts with Ukrainians. Thus, the Jews' participation in the 1922 Sejm elections made matters worse for the attitude of the Ukrainians towards Jews, since the Ukrainians ignored the elections. In 1924, Stanislav Steiger, a law student, was detained on charges of committing a terrorist attempt in Lviv on President Wojciechowski. Although the Ukrainian Military Organization (headed by E. Konovalets) took responsibility for the attack, for a long time the police and the court sticked to the version that Steiger was guilty, because of the growing anti-Semitic campaign. This is the background against which the Polish-Jewish agreement, the so-called “Ugoda" was signed: a Sejm delegate and leader of the "Jewish Colo" faction, Leon Reich, signed an agreement stipulating that in exchange for supporting the government Jews are promised tolerant treatment and certain concessions in their status of a national minority. Although the Ugoda lasted less than a year, until Piłsudski's "May coup" of 1926, it provoked a split in the Jewish political movement itself. ("We Jews must first and foremost pursue Jewish politics," Reich argued. - "There are times in which we have to seek understanding with the government.") This brought about a rejection of the Zionist parties and intensified dislike on the part of Ukrainians ("A united and solid front of assimilationists emerged - not to defend Steiger, but aimed exclusively against the Ukrainian society," wrote the Delo newspaper).

A characteristic view of Ukrainian-Jewish relations at that time is expressed in the "Word of Caution" issued by a Greek Catholic priest Vasily Podolinsky: "...if we were at their home, we would adapt to them, but since they are at ours, let them adapt to us. After all, I am not forbidding them to be and remain what they want to be. We, logically, are masters in our own house, and they are friends. Therefore, they are entitled to delicacy and courtesy from our part, and we to sympathy from their part. Neither we nor they should demand more”. It is important to stress that these are words of a person who had a rather welcoming attitude towards Jews. One can easily imagine the rhetoric of overt detractors of Jewry in a general atmosphere of hatred. By the end of the 1930s, official anti-Semitism (for example, in 1935 the Lviv Polytechnic and in 1937 The Lviv University introduced a "bench ghetto" for Jewish students) and encouragement of Jewish emigration from the country intensified. The Polish authorities made no secret of the fact that it was in the interests of the Jews themselves to leave the country, and the sooner the better. It was the anti-Semitism of the Poles rather than the anti-Semitism of the Ukrainians that Galician Jews saw as a greater threat. It is worth noting that the latter, according to Yaroslav Hrytsak, also underwent significant changes over time, as the emphasis in the Ukrainian national movement shifted from romantic nationalism towards the idea of a multi-ethnic civil nation, where Jews would have a place along other ethnic groups. But this happened only after the Holocaust.

As for the Jews themselves, they repaid both Poles and Ukrainians with distrust and dislike. Thus, the Polish republic approached the 1939 catastrophe with strained interethnic relations.

Lessons of the past—a vision for the future

World War II took a deadly toll on the “thriving complexity" of the multi-ethnic Lviv, with the Jewish population almost completely exterminated (except for those who survived because of the 1939-1941 deportations), and Lviv Poles were repatriated to Poland only after the war. The urban population changed drastically, and the Jews who arrived in the late 1940s and 1950s, as a rule, had not lived in Lviv before the war. They were immigrants from other republics and regions of the Soviet Union. In the post-war decades one cannot speak of Lviv as a multicultural city - it was dominated by a monotonous Soviet cultural landscape.

Over the thirty years of independence, the people of Lviv have done a lot to restore their city to its former diversity and glory as the best place to live (as characters of the cult 1939 film "Vagabonds" by Michał Waszyński sang: "well, where else are people as good as here? " - "only in Lviv! "). This process is still underway, and we do not yet know how it ends. In any case, the logic of modern urbanism tells us that the future lies with cities that create for their residents a space of security, comfort, freedom of self-expression and cooperation that benefits all.