Course

Jews in the Weimar Republic Cinema

Galeen and Golems: Central Images of Expressionist Cinema created by a Jew from Lviv region.

Social Drama and Jewish Question in 1920s and Early 1930s German Cinema

How did the cinema of the time of the Weimar Republic create modern cinema and what is the role of Jews in it?

Erich Pommer

Erich Pommer. Photographer unknown, 1929 / Wikimedia

World War I was at its end. In a desperate attempt to bolster the people's morale, General Erich Ludendorff urged the Defence Ministry of the German Empire to start a film company. In December 1917, the UFA (Universum Film AG) film company was born, funded by the German government, the Defence Ministry and the Deutsche Bank. UFA's mission was to make propaganda films aimed at "forming a common world view for the masses ", but it chose to follow the well-trodden path of commerce instead: making films that make the box office. This is hardly surprising, given that UFA emerged from the country's three leading film companies. The first was Messter Film and its leading German star of the 1910s, Henny Porten. The second was Nordische Film GmbH, the German subsidiary of the Danish Nordisk film company. And lastly, the PAGU film company, where Ernst Lubitsch had just started working in the war years. In the early 1920s, other companies also joined the UFA. Some became part of the conglomerate, while others continued cooperating but retained their independence. In any event, UFA shaped the film industry of the Weimar Republic, spanning the period between 1918 and 1933.

In 1921, the most important “merger" took place, with Decla-Bioskop and its managing director Erich Pommer becoming part of UFA. Pommer was a German Jew who had been involved in film before the war and founded his own film company, Decla, in 1915 while still serving on the Western Front. In 1920 Decla and Bioskop merged and became UFA's chief competitors for a whole year before merging with it. Not only did Pommer continue to run Decla-Bioskop, but he also became UFA's lead producer. Throughout the 1920s, he would go on to produce a dozen masterpieces (including Friedrich Murnau's The Last Man and Faust, Fritz Lang's Metropolis and Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel) while also launching the major trend of 1920s German cinema, Expressionism.

Film Expressionism

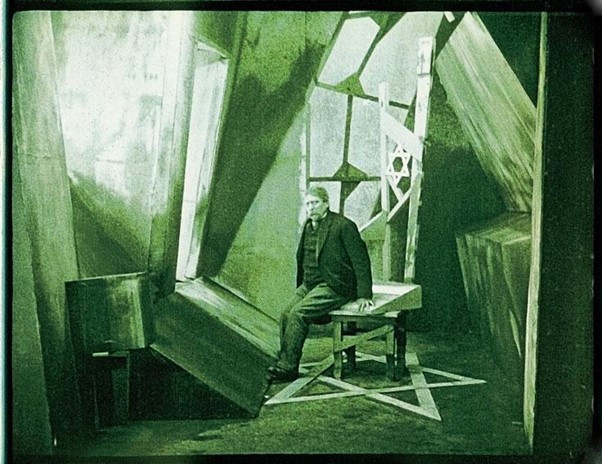

Frame from the film"The study of Dr Caligari" directed by Erich Pommer, 1920 / Wikimedia

Pommer produced The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1920, which was to go down in film history as the first Expressionist film. In the film, Dr Caligari arrives in a small town to perform his strange and uncanny act at the local fair: he revives a somnambulist, Cesare, who predicts the hapless onlookers' future. Cesare predicts the death of one of them, and at the same time, news of murder is heard in the town's streets.

But these are not your typical streets! All their lines are twisted, and the streetlights look like Guernica's electric Sun. artists Hermann Warm, Walter Röhrig and Walter Reimann certainly didn't try to hide that the sets are cardboard. Instead, they highlighted their conventionality and expressiveness.

Contrasting shadows, sharp angles, grotesque interiors and the monsters that populate them - somnambulists (as in Caligari), vampires (Nosferatu) or mere shadows (Warning Shadows) - all this creates a general feeling of unease verging on obsession that is the hallmark of expressionist films.

The film was directed by Robert Wiene (a Jew from Breslau, today's Wroclaw in Poland), and the screenplay was written by Carl Mayer (a Jew from Graz) and Hans Janowitz (a Jew from Poděbrady, today's Czech Republic). Except they were not the first to introduce such a wretched and terrifying creature, born from a mystical plot and resembling Cesare, the somnambulist, to the screen. This had occurred earlier when the war had just begun.

The First Golem

Paul Wegener and Lida Salmonova in the film The Golem,

directed by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen, 1915 / Wikimedia, culture.pl

On January 14, 1915, The Golem premiered in Berlin. The screenplay was by Henrik Galeen.

Galeen (born Wiesenberg) began working as a reporter, struggling to make a living at provincial theaters until he moved from his hometown of Stryi (now Lviv Region) to Berlin. In 1906, he was employed by the renowned theater director Max Reinhardt as his assistant. And in 1914, he embarked with Paul Wegener on The Golem and made his successful debut in the film, not just as a screenwriter: Galeen also co-directed the film and even played one of the main roles - the antique dealer. Paul Wegener plays the Golem, and Guido Seeber, the leading cameraman of the 1920s, was in charge of the photography.

The film was based on the legend of the Prague rabbi Loew and his clay golem, whom the rabbi made and animated to protect the Jewish people from persecution. The Golem was mute, docile and animated by a particular word placed in its chest. Galeen maintained the legend unchanged, except that the film was set in modern times. Now the golem, motionless, was found and taken to an antique dealer, who decided to bring it back to life and use it in his household. Although the film's complete version was lost, occasional footage and the screenplay enable us to reconstruct the meanings that Galeen put into the story.

The protagonist, an antique dealer, was depicted as a typical Eastern European Jew, with his black yarmulke, peyes and seated behind his books. Except that the books were not Torah or Talmud but accounting books. The antique dealer, replaced by the Rabbi in the legend, was a completely different type - a profit-seeking merchant. The Torah was put up in his shop window, and the golem served his private needs. Galeen's attitude seemed critical, calling for integration and leaving the traditions behind. The line with the golem was particularly revealing: the effigy falls in love with the antiques dealer's daughter, but she, naturally, could not reciprocate; moreover, her affections were directed towards a non-Jew, the town baron. And if, at first, the father found this unacceptable, later, when the golem got out of control and smashed everything around it, his daughter's association with the non-Jew no longer strikes the deal as tragic. In the film, the golem is frightening and primarily appears as a force for destruction. In the finale, it falls from the tower and shatters into pieces, as if (self) destroyed by its inappropriateness. But by 1920, this all changed when the second film by Galeen and Wegener, The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920), was released.

Second Golem

Frame from the film 'The Golem: How He Came into the World,'

directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese, 1920 / IMDb

This 1920 film can be considered a prequel to the earlier one - the story was set in 16th-century Prague, and Rabbi Loew was still present. There was also the daughter who fell in love with the King's messenger, a character not mentioned in the legend. And also the golem, who, despite playing the part of the savior of the Jewish people, at some reverted to a path of destruction. What was different, however, was that now it was the stars, and not unrequited love, to blame for his untamed behavior. The Golem spiraled out of control and walked into town. The Golem killed people. He couldn’t seem to find a place for himself. Stepping outside the gates of the Jewish quarter, suddenly he smiled at the sunlight, the meadow, and the children. Everyone was afraid of the golem, but then a little girl came up to him, went to his arms, started playing with the star on his chest ( the star contained the secret word inside it) - and she took it off. The golem dropped dead.

What killed the golem was not rage, revenge, or a curse, but rather his ability to feel, to love - to be "like everyone else" while being different. Rather than a sense of the shattered past from the first film, the second Golem unexpectedly tells us a story about that very Other. And over the 1920s, this story repeated itself more than once, because every expressionist filmmaker could be called an Other, incomprehensible, misunderstood, and different. Certainly, this sense of otherness was directly linked to the post-war depression and the overall identity crisis. Yet it is precisely this image of the Other that is key to finding the Jewish identity in the films written and directed by Jews. Although, on the surface, German society was geared towards integration, especially in large cities, Jews seldom got to "belong". Especially Eastern European Jews, the Ostjude. They were what most often emerged in expressionist characters. Henrik Galeen played an instrumental role in the making of such an interpretation. Not only incorporated a Jewish legend into the expressionist imagery, but he also continued to do so beyond the Golem. He went on to create the decade's most striking characters.

Nosferatu and Knock

Max Schreck in the film 'Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror,' directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, 1922 / Wikimedia

German town of Wisborg. In Nosferatu, there were no sidelines, as there wasn’t Professor Van Helsing, the vampire specialist. Otherwise, the stories were quite similar - Nosferatu traveled from Transylvania to Wisborg, bringing death to this European town. But, as in the case of the golem, the fundamentally important thing was the ending.Galeen and Murnau, the film's directors, portrayed Nosferatu almost like an insect, with its unique way of life and needs. Although Nosferatu was an antagonist, it seemed hardly appropriate to blame him for being a vampire. What complicated things was that Nosferatu fell in love. And, as one might expect, love brought him to his death: failing to keep track of the time, Nosferatu went to see his beloved and ended up being out at dawn, which burned the vampire to ashes.

Nosferatu also suggests an Eastern European outsider. Of course, Galeen did not intend for him to be seen as a Jew. Instead, he conjures up an extreme version of some abstract other, even more terrifying than the golem, yet still capable of love. Being the central character, the antagonist seems to push for a tragic ending. The happy ending, as it is in the film, appears to be merely a subplot denouement. But the reflection on otherness did not stop here. Another very important, albeit supporting character in the film was Nosferatu's servant, waiting for his master to bestow eternal life upon him. His name was Knock, and he was played by Alexander Granach.

From his native village of Verbivtsy, Granach first moved to Lviv, then to Berlin. The writer Arnold Zweig referred to Granach as "the strongest temperament of ", and his friends called him "". In the theater, Granach did not hide his Jewish identity or otherness but rather accentuated it in every possible way. He did the same in Nosferatu. If the film took pity on anyone even more than on Nosferatu, it was on him - Knock. As film historian Margrit Frölich writes about this role: "... it neither excites nor reinforces anti-Semitic sentiments; on the contrary, it reveals their anxiety-ridden nature and ".

Alraune and Waxworks

E.A. Dupont, Paul Leni, Fritz Morishat, John Gottowt, Lore Sello, and

on the white horse to the right, Leo Birinski. Photographer unknown, 1923 / Wikimedia

Galeen himself will direct the next adaptation of the literary work - Hans Heinz Ewers' novel 'Alraune. Alraune, too, was a perfect fit for the character of the other. This was a strange creature, made by Prof. Jakob ten Brinken from a hanged man's seed in a prostitute's womb. It possesd amazing properties, attracting men, good luck and was seemingly impervious. Naturally, just like the golem, Alraune rebelled and, like Nosferatu, fell in love at some point. Galeen invited Paul Wegener to play the role of the Professor; the part of Alraune was performed by Brigitte Helm, who, only a year earlier, had played Maria and her mechanical and evil doppelganger in Lang's Metropolis. Although Alraune and the tall, fair-haired Helm were very far from the Jewish legends and the image of an Eastern European Jewess, nevertheless, by once incorporating the golem into the expressionist imagery, Galeen had irrevocably made Jewish history a part of it. Much like Lubitsch, whose 1910s Jewish lads morphed into the 1920-30s emancipated young women, Alraune was, for Galeen, represented for Galeen a shift in focus rather than a complete departure from the subject.

Alraune was released in 1928, during the twilight of the expressionist movement. By then expressionism had long since shifted from flat sets to multidimensional and much more sophisticated lighting and angles. By the late 1920s, it had definitively left its leading positions behind. However, here, too, Galeen was quicker than the rest. As early as 1924, he wrote the screenplay for Paul Leni's film Waxworks, which was not so much a parody but rather an anthology of the existing film genres, drawing their bottom line. Presented as an almanac, it was divided into three novellas linked by the Waxworks cabinet. Each novella featured a wax figure: the first was about the Arab Caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd, the second was about the Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible, and the third was about serial killer Jack the Ripper. Galeen and Leni brought together historical-costume films, adventure, horror and expressionist aesthetics. There was no otherness here; on the contrary, all characters and genres were easily recognisable to the viewer.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Galeen fled Germany: first to Sweden, then to the UK, then to the States. He tried to make a sound version of The Golem, but nothing came out of it. Had he succeeded, Golem might have learned to speak, but the clay effigy was to remain silent forever.

Kammerspielfilm

and scored by Giuseppe Becce; produced by Rex-Film GmbH studio, 1921 / Mubi.com

The definitive trend for the 1920s German cinema was Expressionism. However, social issues weren't solely addressed using scary creatures or abstract backdrops. The cinema also turned to the streets and the flats of modern cities. The screens saw a flourishing of social dramas of all sorts. Their primary subject for these films was poverty due to post-war hyperinflation, and one of the favorite sub-genres that emerged was Kammerspielfilm, or chamber drama.

In chamber drama, the plot would usually unfold in only a few settings and inside one family. The social backdrop served as the ultimate trigger: even if the characters' actions and feelings were not directly determined by their social status, it was still the environment they lived in that exacerbated all conflict. Simply put, unlike in Expressionist films, the characters were driven to their death not by some abstract Expressionist shadows but by the crumbling walls of their cramped, unwelcoming homes, where they had nowhere to escape from their problems and pain.

As was also the case with expressionist cinema, many important films, exemplary of the genre, were authored by Jewish screenwriters and directors. The most famous of them was probably Lupu Pick.

Born in Romania, his family moved to Germany when he was still a child, and in the mid-1910s, Pick embarked on his career in film, initially as an actor. In 1921, he made his first Kammerspielfilm Shattered, which garnered his considerable success. The simple plot told the story of a track cheker’s family: an inspector seduces the daughter; the devastated mother heads off to church on a very cold night and freezes to death; the father decides to have his revenge and kills the inspector.

The script for the film was written by Karl Mayer, who had worked on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari a year earlier. Obviously, Shattered was still a long way away from social facts, and yet it was gradually becoming attuned to portraying everyday life. You wouldn't find any Jewish motives in this film. In fact, social drama was generally ill at ease with Jewish issues. Jews could write scripts and direct films, but whenever a Jewish character was introduced into a poignant social drama, the story heated up instantly - any conflict in the movie could escalate into an anti-Semitic outburst, and the film itself risked being disfavoured by the producers, who preferred to focus on less controversial themes.

Joyless Street

produced by Sofar-Film studio, 1925 / www.themoviedb.org

In Georg Wilhelm Pabst's 1925 film Joyless Street, all things Jewish were left out of the picture, particularly explicitly. The film's plot was again a drama, except that now it involved not one but several families and, according to conventions of the social theme, was set in the squalid rooms to be found in one joyless street in Vienna. Rather than chamber, the film aspired more towards a novel form, as it was an adaptation of Hugo Bettauer's novel of the same name.

The original text was adapted for the screen by Willy Haas. Haas came from a family of Prague Jews. Following in his father’s footsteps, he went to law school but became increasingly passionate about literature. In the 1910s, he edited and contributed to local magazines. Later, after the First World War, he moved to Berlin and began working as a screenwriter. Taking on Joyless Street, Haas aimed to maximally reduce the novel's romantic sentiment and bring it closer to real life in the streets. He succeeded splendidly, and not just in that.

While working on the script, Haas removed some of the Jewish characteristics that certain characters had in the novel. Instead of reassigning these characteristics to other characters, he made amendments to the script itself. In this way, in the script, a wealthy woman killed by her rival out of jealousy was no longer Jewish, which removed any possible anti-Semitic connotations of the murder in the film. As for a fairly neutral married couple in the novel, Haas turned them into charitable, generous Jews with a difficult past (immigrants). In this case, Haas offered the audience a chance to relate to the characters' Jewishness. Moreover, a Jewish journalist in the novel was replaced by an American soldier.

Once the script got into the hands of the director, Jewish themes disappeared altogether. As Mark Sorkin, the film's editor, a Jew of Russian descent, remembers: "Pabst felt that if he toned down the Jewish thing, the film would prove more profitable and therefore more desirable to his Russian-Jewish investors". Thus, the issue of "visibility" proved pivotal not so much to the film (it turned out great, albeit without Jews), but to the social context of its making. And most importantly, this issue did more than exist - it demanded active action by directors and screenwriters.

City without Jews

The issue of visibility was not limited to fictional characters. Many Jewish immigrants chose not only to conceal their heritage but also to actively assimilate. For example, the renowned German filmmaker Fritz Lang was brought up as a Catholic by his Jewish mother. Robert Wiene, the director of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, converted to Protestantism. Similarly, the journalist and writer Hugo Bettauer, whose parents were Jewish immigrants from Lviv moved to Baden, where Hugo was born, converted to Protestantism. Such choices regarding the shaping of one's identity, reflected on the specifics of the assimilation process, but certainly did not solve the overarching issues, in this case, the general anti-Semitic sentiment and intolerance rampant in German society of the time. What was needed was a different position - one not of hiding but one of speaking out. This outspokenness came with another screen adaptation of Battauer’s novel- The City Without Jews. There, one could not simply leave the Jews out.

Ida Jenbach, a Jewish woman from Miskolc, was in charge of the screenplay. She did not greatly alter the satirical dystopia on how, in one German town, the Christian-Socialist party expels the Jews, after which the town falls into total decay. What she did was merely smoothing it down by making the politician characters more fictional instead of being recognisable (as they were in the novel). The film came out in 1924, two years after the novel's publication. But regardless of Jenbach's efforts to tone the screenplay down, the film still made the NSDAP officials angry. On March 10, 1925, in his magazine's editorial office, Bettauer was shot multiple times by a Nazi party member. By the end of the month, the writer passed away.

Nathan the Wise

Still from the film "Nathan the Wise," directed by Manfred Noa, written by Gotthold

Ephraim Lessing and Hans Kizer, with music by Rabi Abu-Halil, Alesha Zimmerman,

and Willie Schmidt-Gentner. It was produced by Bavaria Film, Filmhaus Bavaria GmbH,

and Münchner Lichtspielkunst AG (Emelka) in 1922.

There were some more conventional screen adaptations, too. For example, in 1922, one of the pacifist play by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise. The story revolves aroundlove and hate between Jews, Templars and Muslims. It was set in twelfth-century Jerusalem. The film kept the original timeline, characters, and messages, except that German screenwriter Hans Kaiser rearranged the order of the scenes and added some battle scenes to enhance the film's comprehensibility. Nevertheless, after the film's premiere in Munich, even this cinematic expression sparked outrage among local Nazi party officials. Although the movie was quite successful, to avoid any unrest, it was pulled off the Bavarian film screens.

The main character, Nathan, a Jew, was played by Werner Kraus, a German actor and an absolute film star. In the 1920s, he starred with all the top directors: he played in Shattered (father) and Joyless Street (heartless butcher). When Hitler came to power, Kraus did not leave Germany and, in 1940, once again played a prominent Jew. This time, it was the lead role in the propaganda movie Jud Süß.

No Man’s Land

Still from the film No Man’S Land, directed and written by Victor Trivas,

Georgi Zhdanov, and Leonhard Frank, with music by Hans Eisler.

Produced by Resco-Filmproduktion, 1931 / www.diepumpe.de

Like Nathan the Wise, No Man’s Land was a pacifist movie. It was directed by Viktor Trivas, a Jew from St. Petersburg. Trivas moved to Germany with his parents in 1925 and worked as a set designer and screenwriter. No Man’s Land was his second work as a director, and it was this work that earned Trivas his fame. It was released in 1931 and was not the only anti-war film of the early 1930s: Pabst had two (the 1930 Westfront, 1918 and the 1931 Comradeship). And while the plot clearly alluded to World War I, one can already sense an anxiety about a new war. And no one knew yet if it would be another World War.

No Man's Land was also significant for its cinematography, as it was highly inventive in its treatment of space (everything, except for a few flashbacks, was shot in one location) and for its treatment of sound. In 1931, sound cinema was only beginning to gain momentum, and one can find numerous experimentations with sound in films of the time. Trivas had such experiments, too, involving languages in the movie - there was more than one. There were five main characters in the film in total. A Frenchman, a German and an Englishman - each spoke his language and could not understand the others; an African man who seemed to understand them all a little, and a Jew from Russia, who was either shell-shocked or deaf-mute and couldn't understand anyone. They all found themselves in the basement of a half-ruined building, somewhere in no man's land, on the neutral strip.

The Jew was not wearing any uniform, so no one knew which army he's from (but the viewers knew that he was a Jew, as we were shown a Jewish wedding in a flashback). In a way, he himself symbolized the no man’s land: the film begins with the Frenchman and the German trying to help him. These soldiers set up their everyday routine, cooked, and slowly got to know each other. But then, a shelling happened because the smoke was coming out of the chimney, forcing them to leave this peaceful place. The movie concludes with an open ending.

The Ancient Law

Still from the movie The Old Law, directed by Edward André Dupont,

written by Paul Reno, composer Philipp Scheller;

studio 'Comedia-Film GmbH', 1923 / www.berlinale.de

Of all the films mentioned above, The Ancient Law (directed by Ewald André Dupont, 1923) touched most closely on the issue of urgent importance for Jewish immigrants. This film tells the story of assimilation and the laws of society (remarkably, of any society). It told the story of a young Jew from Galicia named Baruch Mayer (played by Ernst Deutsch, a young Jew from Prague). The boy dreamt of becoming an actor, but his rabbi father could not accept this whim and insisted that his son continue his studies and dare not leave the shtetl. Baruch ran away, naturally.

He traveled to Vienna, got a job as a handyman in a theater company, and one day, he got lucky - he was given the role of Shakespeare's Romeo. The company performed before the nobles, and even though Baruch was shown in a comic light, with Payot sticking out from under Romeo's hat, he still got noticed by Archduchess Elisabeth Theresia. She did everything she could to promote his future, getting him a place in Vienna's Burgtheater and clearly had feelings for him. But this situation could not continue, and she was commanded to drop her protégé. In her last conversation with Baruch, Elizabeth Theresia sais: "You once told me about your father's ancient law. We, too, are slaves to one ancient law - etiquette."

With that, the film ended rather reassuringly. The father arrived in Vienna, watched his son perform on stage, and forgave him. In contrast to the tragic endings of expressionist films, where society was not ready to accept the other (Golem or Nosferatu), even though he was capable of love, the subject of assimilation transposed into urban settings was given a rather interesting twist. For a Jew, especially an Eastern European Jew, someone who cherished the traditions and often left behind their family or beloved, what was far more important was not to be accepted but to be let go. For a Jew, it was hard to give up the “Ancient law", but the moment he accepted the New Law, things worked out. This idea was reinforced by The Ancient Law and East and West, a comedy directed in neighboring Austria in 1923 by Sidney Goldin, a Jew from Odessa.

Goldin also told an assimilation story of a Polish Jew in Vienna, except that he also drew on his own experience as a Jew coming to the United States. He played one of the roles in the film - a businessman father who had moved to the States. Now, with his daughter (a “modern woman" who was into boxing and had no intention of giving up her pleasures and submitting to patriarchy), he traveled to Poland to attend his niece's wedding. In Poland, an orphaned Talmudic student fell in love with the businessman's daughter, but he's no match for this modern lady, so he had stay behind in the "shtetl" for the time being. But later, he traveled on to Vienna, where he went through a striking transformation - so there could be a happy ending.

Girls in Uniform

Still from the movie 'Girls in Uniform,' directed by Leontine Sagan, written by

Christa Winsloe and Friedrich Dammann, composer Hans-Milde-Maisser,

studio 'Deutsche Film-Gemeinschaft,' 1931. / www.dff.film

In many ways, Girls in Uniform (1931) summed up the decade. It had it all: flawless framing, expressive editing, exceptionally skillful use of sound, but most importantly, it was deeply involved with social issues. The film's director was a Jew, or a Jewess, to be more precise. Leontine Sagan started her career and made a name for herself in the theater. She moved from her native Budapest, studied under Max Reinhardt, and went on to become a theater director. It was at the theater that she first directed Christa Winsloe's play Yesterday and Today, which she would later take to the film screen as Girls in Uniform.

Like Trivas’s film, the film is set during the First World War, but the heroines were far from the battlefront - they were at an officers' daughters boarding school. There, they were being trained for their future as mothers and wives of officers. At school, the discipline was severe, and there was no room for affection. Were it not for the teacher, Fräulein Bernburg, the girls' lives would be unbearable. And that was why, when a new student, Manuella, arrived at the school, she immediately fell in love with her empathetic teacher.

Along with Different from the Others (released in 1919, also in Germany), the film was among the first to address the issue of homosexual love while, of course, speaking of love in general. It also spoke of being misunderstood, alienation, and violence in a totalitarian system (exemplified by the school). Moreover, it was also one of the first, if not the first, school dramas, a model that would be repeatedly used in world cinema (especially similar to it is the style of Soviet school dramas). However, the film's greatest significance lay in Sagan's ability to address pressing issues, all within the backdrop of World War I and the confined, oppressive, and harsh environment of a boarding school. She spoke of herself and of her time. She did not need to be a lesbian to be “different from the others." Merely being a woman in her profession and being Jewish in Germany was hard enough as it was.